Dale Carpenter’s new book, Flagrant Conduct: The Story of Lawrence v. Texas, refocuses much-deserved attention on the Supreme Court’s stunning 2003 ruling, which declared consensual sodomy prohibitions unconstitutional and flung open doors to equality for LGBT people around the nation. Lawrence, litigated before the Supreme Court by Lambda Legal and its Jenner & Block co-counsel, proclaimed that the Constitution protects the liberty of lesbian and gay individuals to engage in sexual conduct and forge personal relationships. The Court’s ringing declaration that its 1986 ruling in Bowers v. Hardwick denying this right “was wrong when it was decided” retracted a devastating precedent that had enshrined and fueled discrimination. Lawrence rejected the premise that lesbian, gay and bisexual people can be criminalized simply because of moral disapproval of their sexuality. In the process, the decision swept away doctrinal as well as symbolic barriers to recognizing that unequal treatment of LGBT people is discrimination that cannot be tolerated in a just society.

Read more about Flagrant Conduct and the Lawrence case.

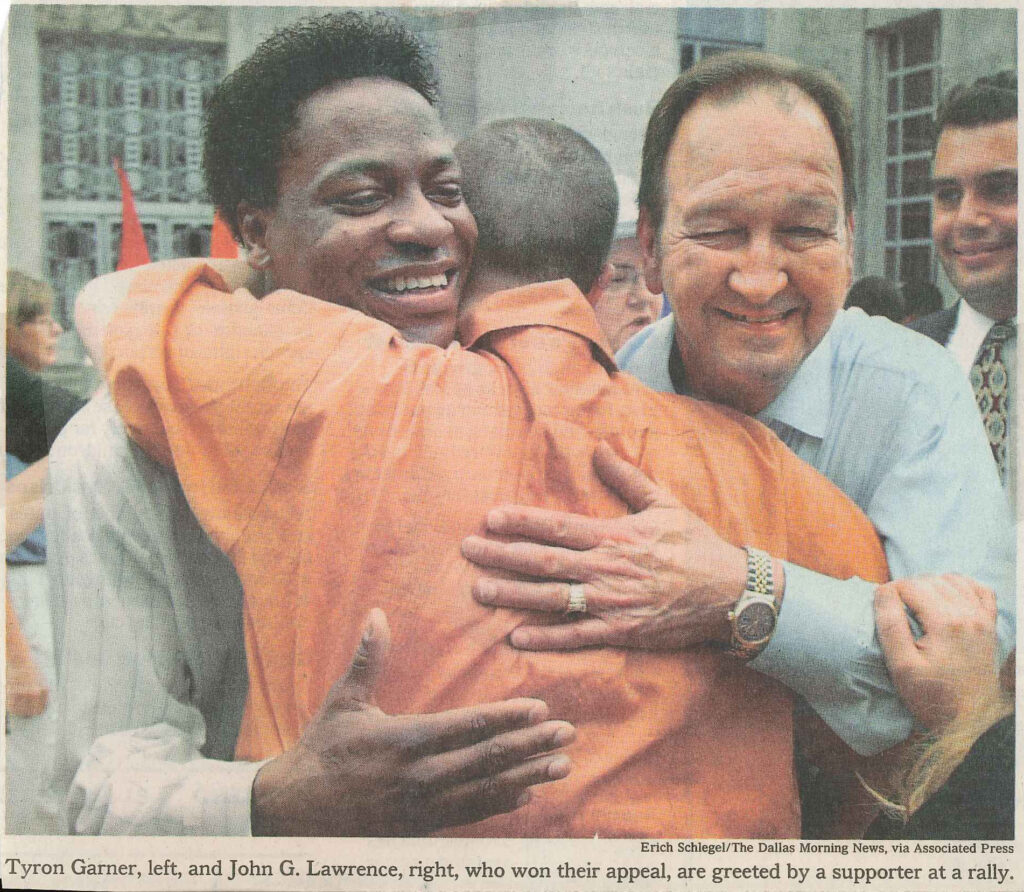

Today Lawrence forms part of the crucial DNA of nearly a decade’s worth of legal victories for LGBT individuals. We saw this just this week in Lambda Legal’s case Gill v. Devlin in federal court in Texas, where police had handcuffed and hauled John Lawrence and Tyron Garner to jail 14 years before. The court held it to be well-settled after Lawrence that a public college violates the equal protection guarantee in refusing a teaching position based on sexual orientation. Lawrence and its reasoning have likewise been essential in landmark cases spanning the nation affirming the right of same-sex couples to marry, beginning with Massachusetts’s ruling in Goodridge just months after Lawrence, to Connecticut’s 2008 Kerrigan decision, to Lambda Legal’s 2010 victory in Iowa in Varnum v. Brien, to the very recent Ninth Circuit ruling in California’s Perry v. Brown. Lawrence was critical to court decisions holding that “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” violated the rights of lesbian and gay military service members, hastening repeal of that discriminatory law. It has been a cornerstone of decisions declaring the federal so-called Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional, including Lambda Legal’s victory last month in a California federal district court in Golinski v. OPM. And the U.S. Supreme Court itself used Lawrence as a building block in its 2010 ruling in Christian Legal Society v. Martinez, upholding a public law school’s refusal to fund a student group that would not admit members who engaged in same-sex conduct, and rejecting the contention that discrimination against those who have same-sex sexual partners is not discrimination against lesbian, gay and bisexual people.

These and many other courts have mined the rich constitutional meaning of Lawrence to render decisions with far-reaching impact. Thus cases like Golinski have applied Lawrence faithfully in concluding that government discrimination against lesbian and gay individuals is so likely derived from prejudice that it must be subjected to heightened judicial scrutiny. Courts too have followed Lawrence’s reasoning to the inexorable conclusion that LGBT people have protected fundamental rights to marry and parent children, no different from other Americans. And many courts have recognized the moral disapproval at the heart of discrimination against LGBT individuals and concluded that such discrimination cannot withstand any level of scrutiny.

Thanks to Lawrence, the courts have been open to the calls of LGBT people for equality and liberty as never before in our nation’s history. While our work in the courts is far from done, without Lawrence we would not be where we are today.