At a time when LGBTQ+ people are being attacked in public and in the courts for living as their authentic selves, representation in books is not only important, it’s necessary. For LGBTQ+ youth in particular, being reflected and represented in the pages of a book is even life-saving.

But more than 3,360 book bans went into effect during the 2022-2023 school year, according to PEN America. Over 40% of them occurred in the state of Florida. Meanwhile, the American Library Association (ALA) said that it saw a record number of attempted book bans in 2022 — a 75% increase compared to the previous year.

These recent book bans disproportionately target a specific group: the LGBTQ+ community. Of the books that made the ALA’s “Most Challenged Books” list, a staggering 53% of them contain LGBTQ+ themes and content. This means vital stories and voices from our community are being erased and silenced.

Our stories belong. Our stories matter. Our stories deserve to be told.

For Banned Books Week (Oct. 1 – Oct. 7), Lambda Legal has invited a panel of LGBTQ+ authors, literary organizations, and bookstores, as well as one of our very own lawyers, to talk about the need for LGBTQ+ stories.

Why is it necessary for LGBTQ+ stories to exist?

Kay Ulanday Barrett (they/he), a poet and essayist based out of New Jersey, a Lambda Literary Finalist, and the winner of a Stonewall Honor Book Award:

Our stories need to exist so that we stay alive and keep existing. Our realities have substance and pulse that reflect humanity. Queer and trans struggles especially overlap with disabled communities, Black communities, histories of migrants, rural and Indigenous communities. More trans and queer voices means we can culturally shift whole understandings which lead to policy shifts and artistic growth. Audre Lorde in “Sister Outsider” wrote, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.”

Stories and writing for us and by us also honor our grief (such as those we’ve lost to the state and AIDS epidemic), uphold ancestral practices (interdependence within sick communities), and help us remember our glory and community triumphs. We need the words to remember who we are and where we want to be, what world we want to examine and how we can sustain joy.

Monica Carter (she/her) of Lambda Literary, a New York-based LGBTQ+ organization whose mission is to nurture and advocate for LGBTQ+ writers:

Without LGBTQ+ stories, we lose the history, vibrancy, and voice of the LGBTQ+ experience throughout time. The voices of the LGBTQ+ community are innumerable and diverse, and if our history and stories are never told, the consequences are real and damaging. LGBTQ+ youth without access to those stories or inclusive curriculum experience higher percentages of feeling unsafe, higher instances of bullying, lower GPAs, and more missed days. Removing access to LGBTQ+ books oppresses our free expression and creative thought. Stories and truth are limitless no matter how we try to legislate one perspective.

Patrick Kern (he/him) of Little District Books, Washington, D.C.’s first LGBTQ+ bookstore since 2009:

LGBTQ+ stories are essential because media is generally a queer person’s first exposure to their own truths. We are generally not born into families with queer parents and siblings so we need stories out there to discover ourselves.

E.R. Anderson (he/they) of Charis Books & More, one of the South’s oldest independent queer and feminist bookstores:

Because queer/trans people exist and our stories are vital to the fabric and history of the world. Especially for young people, how else would you know that you are not alone with your weird thoughts, your fears, your hopes, your loves, if you don’t see them reflected back to you in the image of others? Books allow us, no matter where we live and what we have in the material world, to connect to people and ideas that we might have only dreamed about. Banning LGBTQ books is an intentional form of erasure and a step towards trying to eradicate queer and trans lives.

What is your favorite banned book, and why?

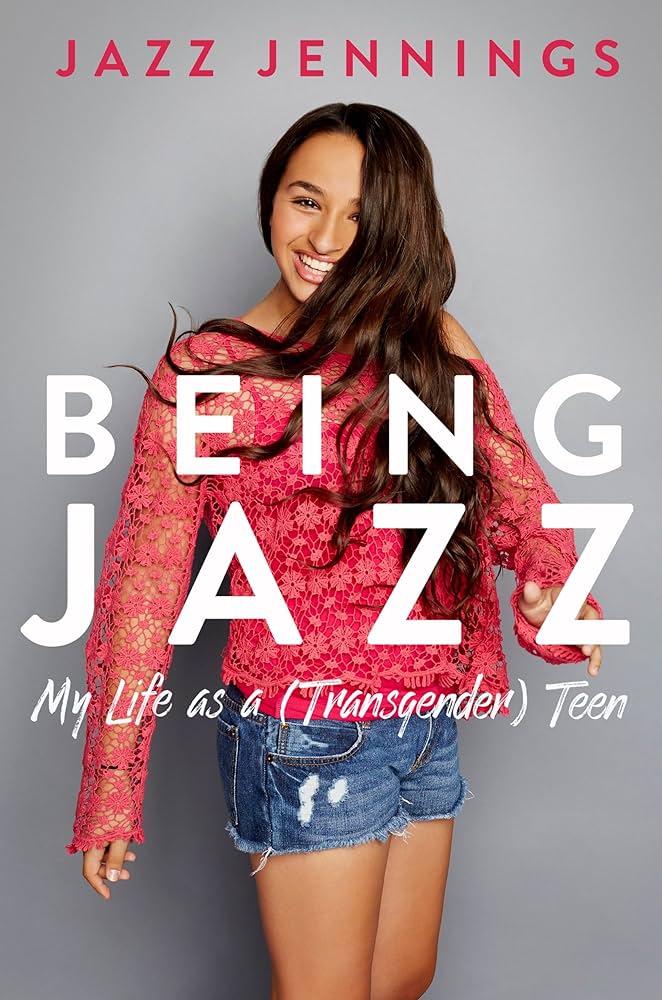

Kay: A few books come to mind. “Being Jazz: My Life As A (Transgender) Teen” by Jazz Jennings is an important book that is banned. When you witness many of the books on banned lists, there’s so few — if any — trans perspectives, moreover from trans women and girls.

Jazz created an accessible and honest conversation in the context of her life and awareness of trans experience. I want more young people to read about trans women of all kinds, and all genres.

A book that comes at the very top of my list is Toni Morrison‘s “The Bluest Eye”. More than stating the obvious of Morrison’s profound and remarkable talent, this book I read in high school and watched a play rendition of in college, addresses white supremacy and Black community in ways that are still erased today.

Charis Books & More: So many of my favorite books have been banned but one of my favorite queer books is Dorothy Alison’s “Bastard Out of Carolina”. It is a foundational text for me as a Southerner and it is the epitome of a truth telling book that might help someone who is struggling — with familial abuse, with poverty, with fundamentalism of all kinds, feel much less alone. It’s a lifeline and so of course it is dangerous. The people banning books ban the lifelines first.

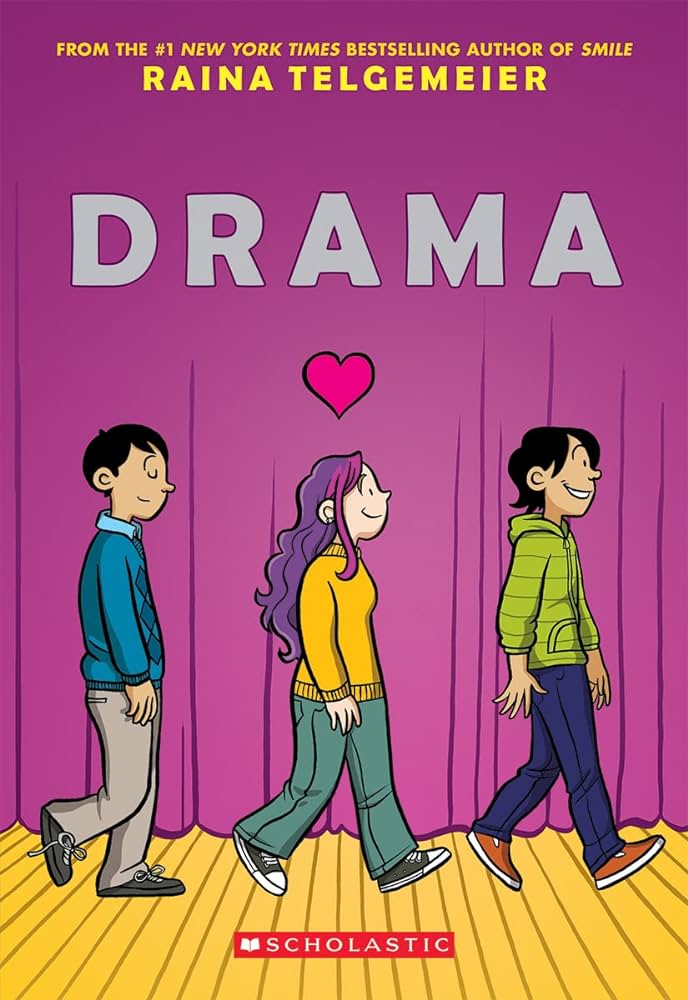

Kell Olson (he/him), Lambda Legal staff attorney: Years ago, my kids fell in love with many of Raina Telgemeier’s books, including “Drama”, and we read them over and over.

I love the way Telgemeier’s young characters struggle with realistic insecurities as they learn how to navigate difficult adolescent years. She keeps the stories both real and lighthearted. “Drama” focuses on a group of students involved in a theater performance and, as far as “inappropriate” content, contains nothing more explicit than a simple stage kiss. Yet it has been frequently banned, presumably because it includes gay characters among the group of friends. Like Telgemeier’s other books, a dominant feature of “Drama” is that these young people find true friends who love them through their most awkward moments. I am so glad this book exists.

Do you remember the first time you saw yourself in an LGBTQ+ book? How did it make you feel?

Lambda Literary: I think the first book where I actually saw someone like myself represented was “Tipping the Velvet” by Sarah Waters (Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, 2000) because it was specifically and purposefully written for a lesbian audience. I felt completely engaged, validated, and seen because it portrayed an honest, intimate relationship between two lesbians. So much of my LGBTQ+ reading experience up to that point was looking for veiled signs of queerness in novels. This was a novel that was intended explicitly for someone like me.

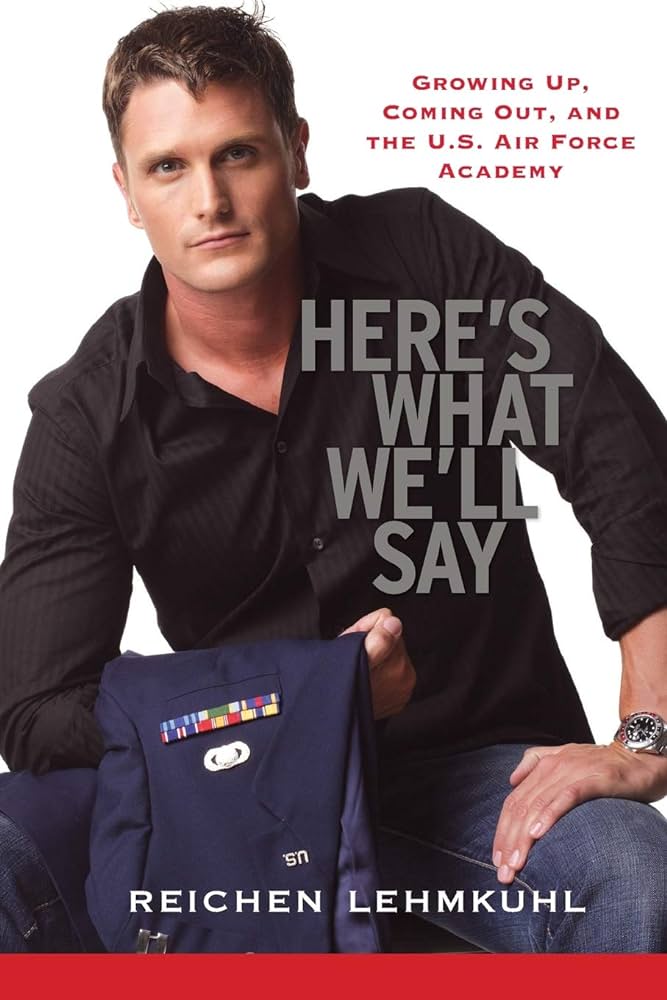

Little District Books: I remember reading “Here’s What We’ll Say” by Reichen Lehmkuhl, a memoir about the author’s time at West Point under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

It described living in the closet like a double life in a way I had never heard it distilled before. The feeling I took away was the relief that the loneliness of the closet does go away.

Check out more of our blogs here, including recent pieces on National Coming Out Day, Latinx Heritage Month, and Bisexual+ Awareness Week.