MEET THE YOUTH CONTRIBUTORS

Emilio, 21, Latiné, trans nonbinary and lives in California;

Emilio (they/them), lives in San Diego, California, where they grew up most of their life in addition to time spent in Tijuana, Mexico. They identify as Latiné, trans nonbinary, neurodivergent, disabled, and had experience in the child welfare, homelessness, and juvenile dependency systems. While entering the foster system at 14, Emilio came out as trans nonbinary; this was a pivotal moment that heavily impacted their time in the foster system and created new obstacles and opportunities for work to be done toward acceptance with their biological family. They shared, “To me being honored and affirmed is really being recognized and holding space for my perspective and identity.” The local LGBT center in San Diego was key to Emilio’s development, to feeling seen, and to being supported. Failures by the system responsible for their welfare are also part of their journey: grievance processes after they were harmed that didn’t bring accountability, and, sadly, adults who never took the time to ask them, “what do you need?” When their judge granted the order for them to start testosterone, it was one of the biggest, most beneficial things that could have happened for them. A Court Appointed Special Advocates (“CASA”) worker also made a difference advocating for them even though the CASA acknowledged she did not fully understand Emilio’s identity. Emilio recommends standing up for TNGD foster youth and making sure they have the crucial supports necessary to survive and thrive when exiting the system: “let[ting] youth have a say in their care, in their lives, and in their existence is just such a vital part of what I would push for.”

Gina, 25, a queer Latina, undocumented, transgender woman and lives in New York

Gina (she/they) takes us to New York City where she currently resides, though she is originally from Southeast Los Angeles, and her home country is Mexico. Gina is 26, undocumented, and immigrated to the U.S. at the age of two. A queer Latina who identifies as a transgender female and has lived experience with homelessness, she is an advocate for immigrant rights, LGBTQ+ rights, environmental justice, social justice, and mental health care. Gina’s family was not really involved with her during her transition, but in the last five years she has created her community and chosen family that affirms her. Gina has navigated systems with very few resources, and it has impacted her development. The onslaught of anti-LGBTQ+ policies and legislation has led to her own advocacy work. The loss of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (“DACA”) also meant additional challenges in New York’s homeless system. Such obstacles can take their toll, so she focuses on her mental health and access to supportive resources. Finding community in marches around Pride has helped her feel alive, welcomed, and connected. Gina recommends that trans and nonbinary youth (i) “travel light,” as the transition from one place to another such as coast to coast or state to state can be challenging and (ii) be sure to bring all documentation, as well as confidence and high intuition about safety. She also recommends making connections, seeking out the services you need for your mental and physical health, and having shelter spaces you can go to for food and necessities. Gina also notes that youth can join advocacy efforts at any time, and she has found community through her advocacy

Jaxsyn, 19, a Two-Spirited Lakota young adult who lives in South Dakota

Jaxsyn (he/him), a 19-year-old Two Spirited man, takes us to South Dakota to share his experience as a Lakota youth in the child welfare system and as someone who has also experienced homelessness at different points in his life. Jaxsyn also identifies as biromantic asexual and is a poet, artist in beadwork, drawing, embroidery, and loves anything else artistic. He enjoys his role as an after-school program teacher. Jaxsyn was raised traditionally by his grandparents. Initially, when he shared his identity with his family, it was not received well or taken seriously. A key person for Jaxsyn was Baylee, a social worker with the local youth task force, who became a safe and supportive adult for Jaxsyn and who showed up for him, advocated for him, and celebrated him. She helped him get information and education for his family and obtain housing. For Jaxsyn, his Lakota way of life and his indigenous identity are central to his being; he didn’t want his Two-Spirit identity to impact that negatively. Fortunately, members of his community made sure to let him know Two-Spirit people have held similar roles in society as he does and that he could still be part of his culture and way of life. Jaxsyn recommends that adults be educated about LGBTQ+ youth so they are able to support them, ensure access to health care, and increase the options for supportive services.

Kayden, 20, white and describes himself as a gender fluid trans masc demi boy, who lives in Texas

Kayden (he/they), 20, grew up in a small, conservative Texas town as a trans youth in the foster system. He is passionate about politics, as well as how mental health and child welfare systems in Texas have impacted him. He describes himself as a gender fluid trans masc demi boy. Kayden shares how staff can support trans and nonbinary youth in meaningful and individualized ways and even advocate with them, which was crucial to his experience in residential settings. Sometimes adults may be the barrier for youth by inserting their subjective idea about what is best for them. In Kayden’s case, that meant caseworkers and advocates basing their opinion on his medical care on their own ideas and not on the recommendations of qualified medical professionals. As a result, Kayden had to wait until he was almost 18 to fully receive the medical care he had every right to access and that had been recommended a full year before. Also, Kayden reminds us that more policy guidance around the limits on religious placements to impose their beliefs on youth is needed. Kayden recommends clear policy guidance on support for TNGD youth so workers and others can look to policy, rather than try to figure it out in the moment.

Shawn, 23, Black trans masculine, gay, was in the foster system in Florida, and now lives in California

Shawn (he/him), 23, who is Black, trans masc, and gay, brings us to Florida to learn about the impact of the social and political climate during his time there. Having experienced the foster system and adoption, Shawn has seen many sides of the child welfare experience. He was in the foster system in Florida and now lives in California, where he is studying sociology in college, but still leaves time for fun with his dog, Cleo.

As a teen, Shawn experienced so-called “conversion therapy” via his church community and their lack of support for celebrating who he is. During this time, he found safety and hope in the school GLBT and Straight Alliance (“GSA”). It was a lot to hold multiple identities and find community support. This has made him think he needs to show up as a tough and strong male. He did receive unconditional support from Florida Youth Shine, Florida’s foster youth alumni group, which made him feel welcome, connected, and supported — highlighting the importance of spaces and groups like this for youth.

Paris, 23, a Black trans woman who lives in Georgia

Paris (she/her), 23, grew up in Georgia in a Christian family and, while in the foster system in Georgia, spent time in the Methodist Home for Children and Youth. Paris identifies as a Black trans female and is a licensed hair stylist. Coming into her own identity as she grew up presented a challenge for Paris’s family to be comfortable with who she is. Fortunately for Paris, entering the child welfare system meant connecting with folks who were supportive, even if they didn’t fully understand her identity. Regardless, she persisted in being herself, wearing what she felt best in, and acting authentically. Had the child welfare system offered services for her family to help them better understand her, she believes they would have accepted them, but they weren’t offered. Paris has felt that, coming from the South, no one was rooting for her, and no one took time to find out what she needed, at least not until a residential staff member and a counselor at the Methodist home did. As an adult, Paris has found support in her peers with shared identity. She recommends that the foster system ensure youth are connected to people like them, allow youth to be themselves, and, when it comes to housing and even shared housing, don’t assume and — ask youth what living arrangements they want or feel comfortable with.

Tyler, 18, a white trans man who lives in Oregon

Tyler (he/they), 18, lives in Oregon, where he experienced government system-involvement as a trans male. Tyler is in high school and working on his diploma in hopes of going to college to support others’ mental health as a gender therapist. Tyler loves nature, abstract art, and anything artistic that inspires him. He was involved with the juvenile legal system and did not experience full support for who he is. Both residents and staff in juvenile detention settings would say disrespectful things and when he reported mistreatment, staff wouldn’t do anything about it — they claimed if they didn’t see it happen, they couldn’t help, even when they were in the same room. Fortunately, detention staff did let Tyler reside in the male-only unit and would check with Tyler on whom he felt most comfortable with during pat-down searches. Even though staff misgendered him and got upset about being corrected, Tyler explains he knows who he is, and staff couldn’t take that away from him, which is what mattered. Tyler also had a very supportive attorney who made a difference in his care and getting access to the gender-affirming medical treatment he needed. Without question, Tyler has found support in his friends, who continue to be a source of support. Tyler recommends having units specific to LGBTQ+ or trans people in detention facilities, having access to a supportive therapist and staff while involved with the juvenile legal system, and asking youth their preferences and how they are doing, something that he always appreciated.

- Elliott Hinkle a trans masculine nonbinary person with experience in Wyoming’s foster care system, conducted telephonic and Zoom interviews with our seven TNGD youth contributors over the course of 2023 and asked all youth contributors the same series of questions around their identity, experiences in care they felt comfortable sharing, whether they had an adult in their lives who was supportive of their identity, whether they were able to define their social and medical transition, and what recommendations they had for systemic improvement. Each youth contributor was compensated for their time participating in interviews with Elliott and reviewing their contributions to this report.

- TNGD—transgender (or trans), nonbinary, gender diverse. Used throughout the report, except where cited research uses other terms such as TGNC (transgender, gender nonconforming). Since cultural norms around gender still negatively impact youth who express themselves outside of those norms, the authors emphasize that every individual is unique and there is no one “correct” way to identify or express oneself.

- LGBTQ+ emphasizes that there are a variety of ways people identify or describe themselves in addition to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning. For example, youth from some indigenous communities may identify as Two Spirit. For more information about the concepts of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (“SOGIE”) or terms youth may use to describe or identify themselves, please see https://cssp.org/resource/key-equity-terms-concepts/. Because people use labels in different ways, or reject labels altogether, the authors recommend that best practice is to honor the language individuals use to describe themselves. Uses of other acronyms in the text are used to reflect research particular to that instance in the text.

- The authors use “juvenile legal” to refer to the system where youth are charged with delinquencies and may face a range of interventions, requirements, and restrictions on their behavior and liberty including short and long-term incarceration or informal conduct conditions or formal probation requirements. Youth under 18 may be treated within juvenile systems or adult criminal systems depending on the jurisdiction and type and severity of delinquency or crime alleged. The authors do not use “juvenile justice” due to the system being profoundly unjust for youth for a variety of reasons, including the overrepresentation and disparately harmful treatment of youth of color, LGBTQ+ youth, and LGBTQ+ youth of color.

A CALL TO ACTION FROM THE YOUTH CONTRIBUTORS

As Paris said, “Having an adult who’s letting you be yourself . . . builds up your confidence.” Our lived experience contributors’ experiences related to respect for their identity and expression informed their recommendations for system improvement. Recent anti-LGBTQ+1 laws and policies at the state level caused emotional harm, concern about accessing needed services, and anxiety and worry for their TNGD2 peers in impacted states.

- Finding affirmation of and respect for nonbinary identity in services, programs, and housing that often are sex-segregated and gender binary was challenging.

- For Shawn, Gina, and Jaxsyn, navigating discrimination and societal inequities around multiple aspects of their identity such as race, culture, and immigration status made feeling safe, finding support, or securing services more difficult.

- Emilio faced harm and discrimination in a group home setting, and staff did not help or hold other youth accountable for their actions that caused Emilio harm. Similarly, Tyler faced harassment in detention from other residents that staff did not address.

- Kayden and Emilio shared that religious messages condemning or pathologizing LGBTQ+ people cause harm;

- Conversely, policies and practices that allowed youth contributors to embrace their race, culture, sexual orientation, and gender identity simultaneously were welcome and positive.

Based on these experiences, they have the following recommendations:

- Kayden suggests child welfare agencies create clear policies, so staff have step-by-step instructions to follow on how to support LGBTQ+ youth.

- Kayden also wants agencies to uphold stricter guidelines around religious placements, so youth are not forced to attend church unwillingly and to provide youth with alternative options that support their identity and culture.

- Paris wants youth to have access to gender inclusive restrooms, facilities, and placements consistent with their preference and where they feel most safe.

To support youth contributors’ recommendations, federal policymakers should take the following actions:

- The White House should issue an update on progress made towards mandates set out in President Biden’s January 20213 and June 20224 LGBTQ+ executive orders and set a timeline for agencies to complete outstanding recommendations.

- Congress should pass the Equality Act5 and the John Lewis Every Child Deserves a Family Act.6

- The Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) and the Administration for Children and Families (“ACF”) should:

- Promulgate federal regulations that fully protect LGBTQ+ youth and families from discrimination and harm while interacting with the child welfare system, including requiring service providers to be competent, supportive, and affirming.

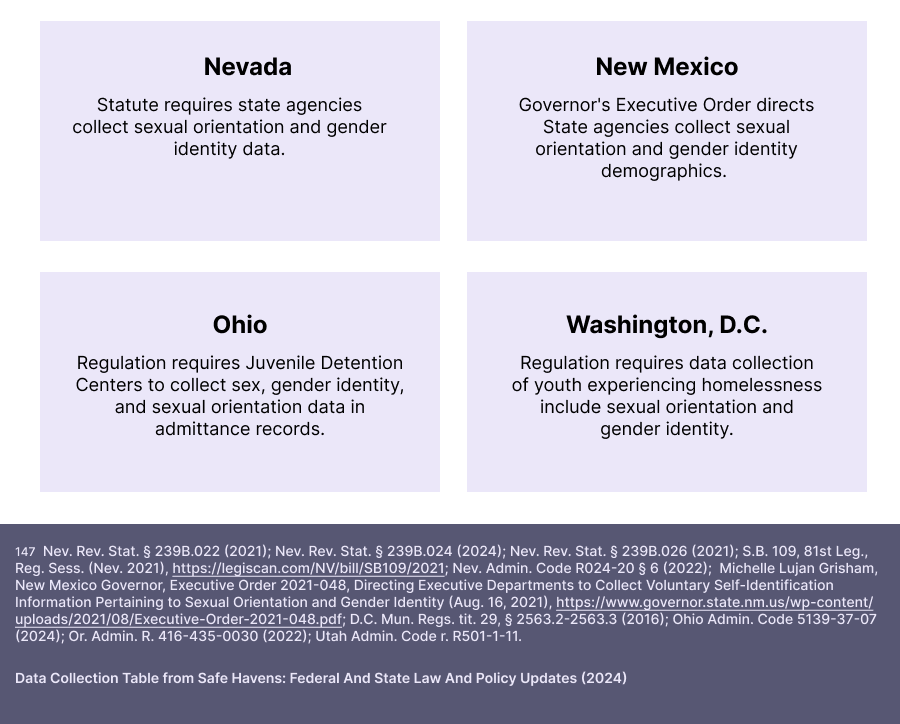

- Collect SOGI (Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity) data for youth and families who chose to voluntarily disclose.

- Provide proactive technical assistance to child welfare systems to facilitate policy and practice guidance improvement, develop and provide training for agency staff and service providers, enact robust accountability measures, safely and respectfully collect SOGI data, and engage with TNGD youth with lived experience in development and implementation in all of these areas.

- Issue guidance that HHS is enforcing nondiscrimination protections in the Runaway and Homeless Youth Rule and offer developmentally appropriate information to youth in HHS-funded Runaway and Homeless Youth programs about their rights and how to file an HHS Office of Civil Rights complaint if they experience discrimination.

- The Office of Justice Programs (“OJP”) and Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (“OJJDP”) should:

- Promulgate a regulation protecting youth from discrimination on the basis of sex, including sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender stereotyping in programs funded under the Safe Streets Act and Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act.

- Continue to fund and support the Pride Justice Resource Center (for justice involved LGBTQ2S+ youth) for Justice Involved Youth to provide training and technical assistance to adults working with youth in the juvenile legal system.7

To support the youth contributors’ recommendations, state policymakers should:

- Repeal laws, agency policy, and rulemaking that harm TNGD youth;

- Enact laws and promulgate regulations that promote the well-being of TNGD youth and protect them from harm;

- Partner directly with TNGD systems-involved youth to develop strategies informed by their lived experience for how to affirm their identities to form the basis for system improvements to address their needs while in care;

- Fund and facilitate research on TNGD youth in out-of-home systems of care to inform empirically supported strategies to combat disproportionality and improve healthcare access; and

- Develop policies that support and affirm nonbinary youth in out-of-home systems.

Endnotes

1. LGBTQ+ emphasizes that there are a variety of ways people identify or describe themselves in addition to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning. For example, youth from some indigenous communities may identify as Two Spirit. For more information about the concepts of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (“SOGIE”) or terms youth may use to describe or identify themselves, please see https://cssp.org/resource/key-equity-terms-concepts/. Because people use labels in different ways, or reject labels altogether, the authors recommend that best practice is to honor the language individuals use to describe themselves. Uses of other acronyms in the text are used to reflect research particular to that instance in the text.

2. TNGD—transgender (or trans), nonbinary, gender diverse. Used throughout the report, except where cited research uses other terms such as TGNC (transgender, gender nonconforming). Since, cultural norms around gender still negatively impact youth who express themselves outside of those norms, the authors emphasize that every individual is unique and there is no one “correct” way to identify or express oneself.

3. Exec. Order No. 13988 Executive Order on Preventing and Combating Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity or Sexual Orientation, 86 Fed. Reg. 7023 (Jan. 20, 2021), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/25/2021-01761/preventing-and-combating-discrimination-on-the-basis-of-gender-identity-or-sexual-orientation.

4. Exec. Order No. 14075 Executive Order on Advancing Equality for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Individuals, 87 Fed. Reg. 37189 (June 15, 2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/FR-2022-06-21/2022-13391.

5. The Equality Act, Human Rights Committee, https://www.hrc.org/resources/equality

6. About the John Lewis Every Child Deserves a Family Act, Every Child Deserves a Family, https://everychilddeservesafamily.com/about-ecdf-act.

7.The authors use “juvenile legal” to refer to the system where youth are charged with delinquencies and may face a range of interventions, requirements, and restrictions on their behavior and liberty including short and long-term incarceration or informal conduct conditions or formal probation requirements. Youth under 18 may be treated within juvenile systems or adult criminal systems depending on the jurisdiction and type and severity of delinquency or crime alleged. The authors do not use “juvenile justice” due to the system being profoundly unjust for youth for a variety or reason, including, the overrepresentation and disparately harmful treatment of youth of color, LGBTQ+ youth, and LGBTQ+ youth of color.

As Shawn said, “My family was not accepting of me being LGBTQ at all. I feel like all foster families, or families in general should accept any services that could help their child. If there [were] services available, and [my family] were more accepting, I definitely would have appreciated guidance on all that.” Our lived experience contributors’ experiences related to respect and affirmation by their families and caregivers informed their recommendations for system improvement. They shared the following:

- They would have welcomed, but often did not receive, services that may have helped family members and foster and adoptive families accept them for who they are.

- Offer families, including kin, and foster and adoptive families support and services to help them reduce rejecting behaviors and promote acceptance of all aspects of a youth’s identity.

To support youth contributors’ recommendations, both federal and state policymakers should:

- Promote family health, including culturally responsive, community-based programs designed to promote acceptance of LGBTQ+ youth by their families and caretakers and reduce rejecting behaviors.

- Allocate resources to and provide training in youth acceptance programs and training to avoid out-of-home placement.

- Allocate resources to provide social education on nonbinary identities.

To support youth contributors’ recommendations, at the federal level:

- ACF should ensure that state child welfare agency plans and resulting work required by the Family First Prevention Services Act is inclusive of LGBTQ+ children and youth.

- ACF, OJJDP, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”) should coordinate with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (“SAMHSA”) to fund additional community-based, culturally informed mental health services, including those that support families in reducing rejecting behaviors and supporting their LGBTQ+ children, and provide funding at a level that meets the need.

- OJP and OJJDP should fund additional research regarding programs that are effective in reducing system-involvement for LGBTQ+ youth of color and their outcomes and experiences once system-involved and additional research regarding the experiences of LGBTQ+ youth engaging in survival sex.8

To support youth contributors’ recommendations state policymakers should:

- Promulgate regulations that require culturally inclusive prevention efforts specific to LGBTQ+ youth, including programs designed to reducing rejecting behaviors by family members and promote acceptance of youth by family and in community.

- Enact laws and policies that require implementation of services and programs to promote acceptance of youth by their parents in the context of child welfare, juvenile legal, and youth homelessness services.

- Ensure efforts to reduce racial disproportionality in child welfare and juvenile legal systems are sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (“SOGIE”) inclusive.

Endnotes

8. The authors of Surviving the Streets of New York describe the terms “youth engaged in survival sex” and “youth who exchange sex for money and/or material goods (e.g., shelter, food, and drugs)” to “reflect young people’s experiences of involvement in the commercial sex market in their own terms. These terms describe a behavior as opposed to labeling the youth themselves.” See Meredith Dank et al., Surviving the Streets of New York: Experiences of LGBTQ Youth, YMSM, and YWSW Engaged in Survival Sex, Urban Institute (Feb. 2015), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/42186/2000119-Surviving-the-Streets-of-New-York.pdf.

As Emilio said, “[T]he biggest thing that helped me was being around other people like me or around other people who understood what it was like to walk around like me, to exist like me.” Our lived experience contributors’ experiences related to support from adults who affirmed their identities and connection to peers and mentors in the LGBTQ+ community informed their recommendations for system improvement. They shared the following:

- Emilio, Jaxsyn, Paris, and Tyler all had at least one adult in their lives who listened, learned, and supported them and advocated with them to get additional services or support they needed.

- Shawn found support in organizations that advocate for youth in foster care and Gina in organizations that advocate for youth and young adults experiencing homelessness in their states.

- Kayden was in a group home where staff were supportive of his identity and allowed him to have input around his placement.

- Emilio found community when connected to their local LGBTQ+ center, and Gina’s participation in Pride events helped her find support from peers.

- Paris was not connected to other transgender girls or women while system-involved but has found support in her community as an adult.

As a result of these experiences, they have the following recommendations:

- Youth should receive support from all adults while involved in public systems.

- Adults working with system-involved TNGD youth should ensure that youth are connected to TNGD peers and mentors and to LGBTQ+ community organizations that are also supportive of their gender identity and expression, race, culture, immigration status, ability, and other aspects of their identity.

To support the youth contributors’ recommendations, at the federal level:

- ACF should promulgate federal regulation to ensure child welfare agencies connect youth to supportive services and establish meaningful measures to monitor whether youth are connected to adults who are supportive of their identity and expression.

- OJJDP should work through the Pride Justice Center to work with state agencies and probation offices to connect with LGBTQ+ community resources and LGBTQ+-affirming service providers.

To support the youth contributors’ recommendations, state policymakers should:

- Require through regulation or agency policy that youth be connected to adults and community groups that are supportive of their identity.

- Provide training to agency staff, case managers and other providers about the importance to TNGD youth of being connected to an adult who is supportive of their identity and expression.

Tyler said, “I had a therapist that was very supportive . . . and very helpful. When I was [on the detention unit” I couldn’t’ really express my needs . . . and [the therapist] was like, ‘Hey, talk with me first, and we’ll help you get your needs across.” Our lived experience contributors’ experiences related to physical and mental health care while in intervening public systems informed their recommendations for system improvement. Our lived experience contributors shared the following:

- Kayden shared that he faced challenges accessing gender-affirming medical care and that adults who were not mental health care practitioners or doctors substituted their own judgment about his needs rather than following guidance from qualified professionals.

- Tyler also faced barriers accessing gender-affirming medical care while involved in the juvenile legal system, but his attorney was helpful in navigating the legal process required for parent or legal guardian consent and court approval.

- For Emilio, going through the court process to get approval to begin gender-affirming medical care was one of the best things that happened for them because they were listened to and got what they really needed.

- Gina faced challenges accessing supportive mental health care as an undocumented person.

To support the youth contributors’ recommendations:

- ACF, OJJDP, and HUD should offer guidance to child welfare and juvenile legal agencies and providers serving youth experiencing homelessness on how to navigate state-based bans on gender-affirming medical care while upholding obligations under federal law and, where applicable, the constitutional rights of children in state custody.

- ACF should promulgate a regulation requiring child welfare agencies to connect youth to support services and to ensure youth receive recommended mental and medical health care from qualified providers.

To support the youth contributors’ recommendations, state policymakers should:

- Repeal laws that bar access to gender-affirming medical care consistent with recommendations from qualified providers.

- Monitor litigation and evaluate existing laws to ensure youth can access care in other states if doing so is not prohibited by law in the state where youth currently live.

- Inventory existing mental health and medical care providers to ensure youth do not face harm and discrimination and require contract mental and medical health care providers be trained and competent.

Endnotes

1. LGBTQ+ emphasizes that there are a variety of ways people identify or describe themselves in addition to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning. For example, youth from some indigenous communities may identify as Two Spirit. For more information about the concepts of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (“SOGIE”) or terms youth may use to describe or identify themselves, please see https://cssp.org/resource/key-equity-terms-concepts/. Because people use labels in different ways, or reject labels altogether, the authors recommend that best practice is to honor the language individuals use to describe themselves. Uses of other acronyms in the text are used to reflect research particular to that instance in the text.

2. TNGD—transgender (or trans), nonbinary, gender diverse. Used throughout the report, except where cited research uses other terms such as TGNC (transgender, gender nonconforming). Since, cultural norms around gender still negatively impact youth who express themselves outside of those norms, the authors emphasize that every individual is unique and there is no one “correct” way to identify or express oneself.

3. Exec. Order No. 13988 Executive Order on Preventing and Combating Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity or Sexual Orientation, 86 Fed. Reg. 7023 (Jan. 20, 2021), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/25/2021-01761/preventing-and-combating-discrimination-on-the-basis-of-gender-identity-or-sexual-orientation.

4. Exec. Order No. 14075 Executive Order on Advancing Equality for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Individuals, 87 Fed. Reg. 37189 (June 15, 2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/FR-2022-06-21/2022-13391.

5. The Equality Act, Human Rights Committee, https://www.hrc.org/resources/equality

6. About the John Lewis Every Child Deserves a Family Act, Every Child Deserves a Family, https://everychilddeservesafamily.com/about-ecdf-act.

7.The authors use “juvenile legal” to refer to the system where youth are charged with delinquencies and may face a range of interventions, requirements, and restrictions on their behavior and liberty including short and long-term incarceration or informal conduct conditions or formal probation requirements. Youth under 18 may be treated within juvenile systems or adult criminal systems depending on the jurisdiction and type and severity of delinquency or crime alleged. The authors do not use “juvenile justice” due to the system being profoundly unjust for youth for a variety or reason, including, the overrepresentation and disparately harmful treatment of youth of color, LGBTQ+ youth, and LGBTQ+ youth of color.

8. The authors of Surviving the Streets of New York describe the terms “youth engaged in survival sex” and “youth who exchange sex for money and/or material goods (e.g., shelter, food, and drugs)” to “reflect young people’s experiences of involvement in the commercial sex market in their own terms. These terms describe a behavior as opposed to labeling the youth themselves.” See Meredith Dank et al., Surviving the Streets of New York: Experiences of LGBTQ Youth, YMSM, and YWSW Engaged in Survival Sex, Urban Institute (Feb. 2015), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/42186/2000119-Surviving-the-Streets-of-New-York.pdf.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

“People who impacted me the most were the people who took that extra little step to just … show me that I mattered to them. I’m not just a youth in system, but I’m a youth in system that was really handling all sorts of things that they really shouldn’t have had to endure in the first place. Understanding, empathizing and advocating for these kiddos is just what makes the biggest impact and what made the biggest impact for me was just people who wanted, who genuinely, genuinely wanted to fight for me. And to listen to what I needed to fight for myself.”

– Emilio (they/them), Youth Contributor

As a nation, we owe all youth, including transgender, nonbinary, and gender diverse (“TNGD”)1 youth, the opportunity to thrive and exist in homes, schools, and communities, that support their healthy development. We must implement policies that reflect this commitment to youth and ensure it is not conditional on race, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, immigration status, or any other element of identity

The research is clear: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+)2 youth thrive when their identities are respected, they are safe from emotional and physical victimization, they have access to programs and physical spaces consistent with their identity, and they receive love and support from their families and communities. Yet, recent federal and state attacks have threatened LGBTQ+ youth’s well-being, and data clearly highlights that as a nation we are failing TNGD youth in particular. In 2022 and 2023, state legislatures set records for pursuing anti-LGBTQ+ legislation3 and are on track to do the same in 2024;4 in 28 states, a majority of these attacks include laws and policies specifically targeting TNGD youth.5 TNGD youth face extreme barriers to their safety and well-being and in some places, daily assaults on their health – for example, with some states restricting access to affirming health care, including banning gender-affirming care. While in some communities, there may not be an explicit attack on the health, well-being, and safety of TNGD youth, data clearly highlights the gap in community-based supports for these youth and their families, seen through the significant overrepresentation of TNGD in child welfare, juvenile legal,6 and homeless systems.

When they become involved in these out-of-home systems, these youth experience physical and mental harm, exclusion from services, and instability that lead to poor outcomes when they leave these systems. Importantly, TNGD and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (“LGBQ+”) youth do not experience worse outcomes or more system-involvement because they identify as TNGD or LGBQ+, but due to the compounding impact of stigma and societal inequities, racism, and misogyny.

We owe TNGD youth better. We owe youth and their families community-based supports that address dynamics that may lead to out-of-home systems; and when youth are in out-of-home systems, we have a responsibility – including a legal responsibility – to promote their safety, health, and well-being. Policymakers and system administrators must take action. They must work to create and implement policies and resources that support TNGD youth in their communities and eliminate harm for youth who are currently system-involved. These policies must center equity, reflect the experiences of TNGD youth, be based on research and science, and include structures that hold systems accountable to youth, thereby creating conditions for TNGD youth to thrive.

Public Systems Are Failing TNGD Youth

Too many youth and families are separated, experiencing homelessness, or involved with juvenile and criminal legal systems due to lack of affordable housing, living wages, and community supports. Much of the research since Safe Havens I confirms prior findings that LGBTQ+ youth are over-represented in child welfare, juvenile legal, and homeless systems compared to their non-LGBTQ+ peers; are predominately youth of color; and have worse experiences while in out-of-home systems. These experiences and outcomes are not inherent in being TNGD but are a result of systemic and societal failure to support TNGD youth. These failures demonstrate that TNGD youth need more supportive policies in place.

Once in these systems, TNGD youth are often failed yet again, and face enormous barriers to accessing support, care, and having their identities affirmed, despite systems’ legal requirements to support the well-being of the youth in their custody, promote their rehabilitation, or provide safe and supportive housing. Youth and families do not get the support they need and experience harm from the system itself. TNGD youth must navigate complex, underfunded, and disjointed social and economic support systems as they try to find family and community acceptance, secure safe and affordable housing, pursue their education, find employment, and access health care – all in the context of public policies that often deny their identities.

These systems and services, which should be robust and affirm and support TNGD youth, too often fail to meet their needs. Discriminatory policies not only marginalize TNGD youth and keep them from crucial supports, but also stigmatize and criminalize their identities and actions. Further, TNGD youth are also impacted by ongoing bias, prejudice, and discrimination in society, which causes elevated rates of suicidal ideation and substance use, among other negative health outcomes. For TNGD youth of color, these barriers are exacerbated by discrimination and systemic racism in public programs.7

Policy Must Affirm Youth Identities and Center Their Experiences

Latest research confirms what countless prior studies have found: for transgender, nonbinary, and gender diverse youth to thrive, they need more than safety from overt bigotry and exclusion; they need explicit affirmation. This means respect, love, and support from their families and communities, physical and emotional safety, and access to programs and facilities, such as restrooms and housing, consistent with their identity. For law and policy to meaningfully affirm and protect TNGD youth, policymakers and administrators must rely on the experiences of TNGD youth who have been in out-of-home systems. To support those youth who are currently in juvenile legal, child welfare, and youth homelessness systems, we must implement policies and practices that promote and affirm the identities of TNGD youth, meet young people where they are and in ways that are responsive to their needs, including by letting them define their own identities, address chronic challenges by aligning practice with professional standards, and support youth to thrive in today’s hostile political environment.

New and Continuing Challenges For TNGD Youth: An Update

During the last 20 years, research and information shared in our work with youth has documented overrepresentation of LGBQ+ and TNGD youth in out-of-home systems, but little concentrated effort has been made to safely prevent system-involvement and provide supports to families, who may be struggling, to accept youth. Policymakers should focus efforts on preventing system-involvement and supporting youth in their communities by 1) following the recommendations of TNGD youth with lived experience in these systems, 2) basing policies on science and research rather than stigma, 3) eliminating harm within public systems, and 4) implementing laws and policies that are supportive to TNGD youth.

As highlighted by Safe Havens II youth contributors, who share their lived experience and a call to action for systemic improvement in this report, since the publication of Safe Havens I in 2017, TNGD youth in particular face new challenges as a result of an onslaught of political attacks on their identities and well-being. In the wake of advances in the law for LGBTQ+ people and U.S. Supreme Court decisions establishing marriage equality for same-sex couples, the Trump Administration made multiple attempts to limit or erase LGBTQ+ rights, with many focused on TNGD people.8 In 2022 and 2023, state legislatures increased their attacks on LGBTQ+ youth. Specifically, 2023 eclipsed the record set in 2022 for most anti-LGBTQ+ bills, with over 500 anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced in state legislatures and 84 becoming law.9 The first quarter of 2024 saw over 400 anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced across the country.10 Tyler, a youth contributor, said, “It mentally affects me because . . . my community isn’t being protected. Other trans people . . . can’t get the support they need and . . . it makes me sad[.]”

Twenty-eight states now have harmful laws or policies in place specifically targeting TNGD youth11 in health care access, school curricula, parental notification requirements, restroom and facility access, and sports participation. This government sanctioned discrimination harms not only TNGD youth, but also all youth who also face the systemic consequences of such hatred. For system-involved TNGD youth, these new laws and policies layer additional harm when youth are not able, for example, to travel to another state for necessary medical care without agency permission or lack the financial resources to do so. Rhetoric and misinformation have created a chilling effect on affirmation of youth. Professionals, including teachers, doctors, and social workers, are now fearful of being reported and having their licenses revoked.

Efforts To Affirm, Support, And Protect TNGD Youth: An Update

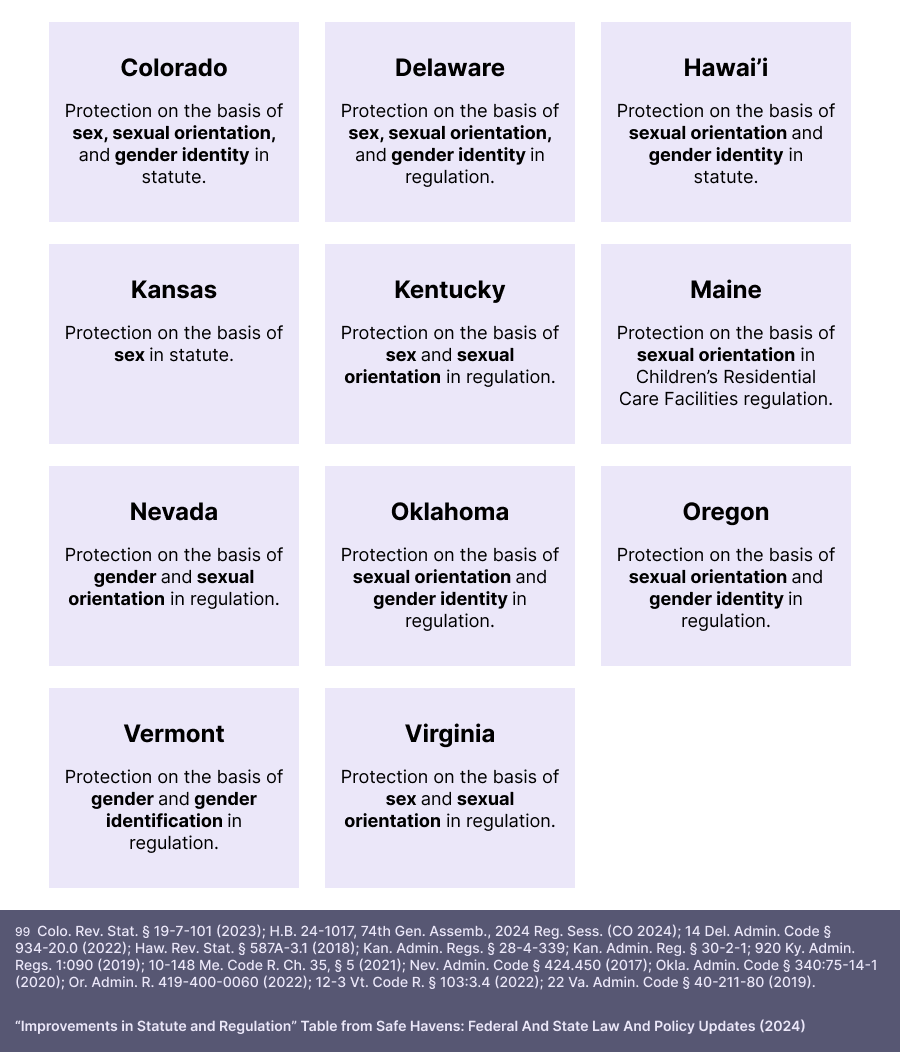

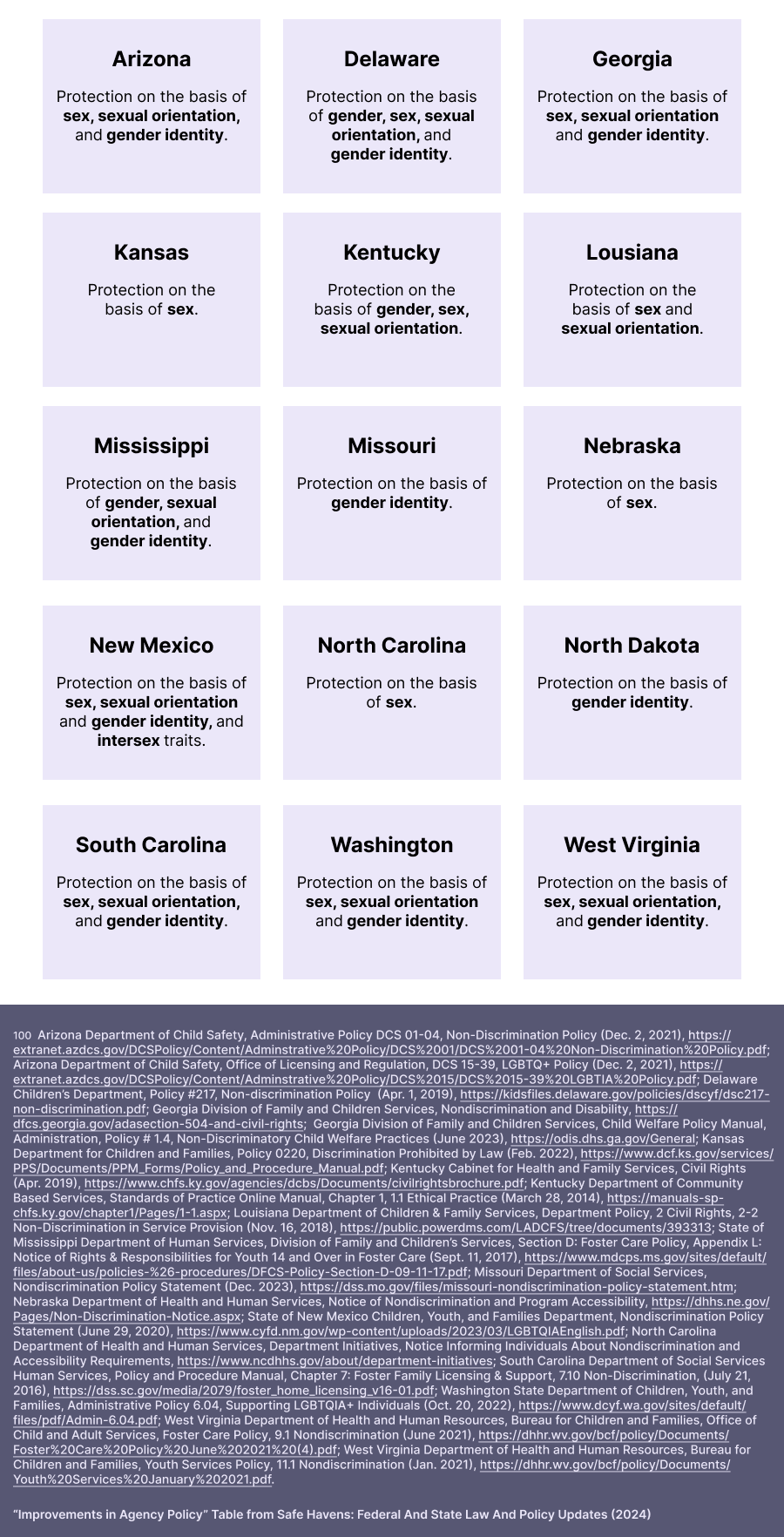

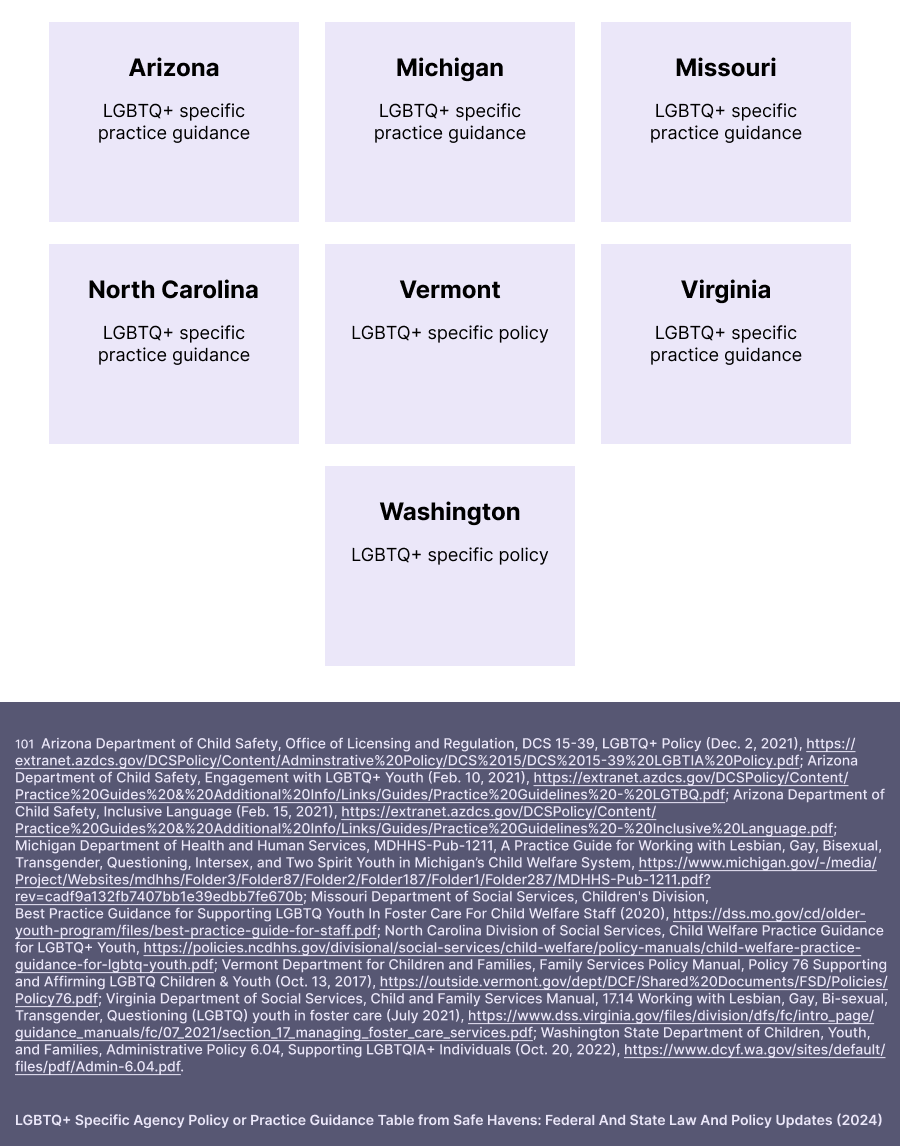

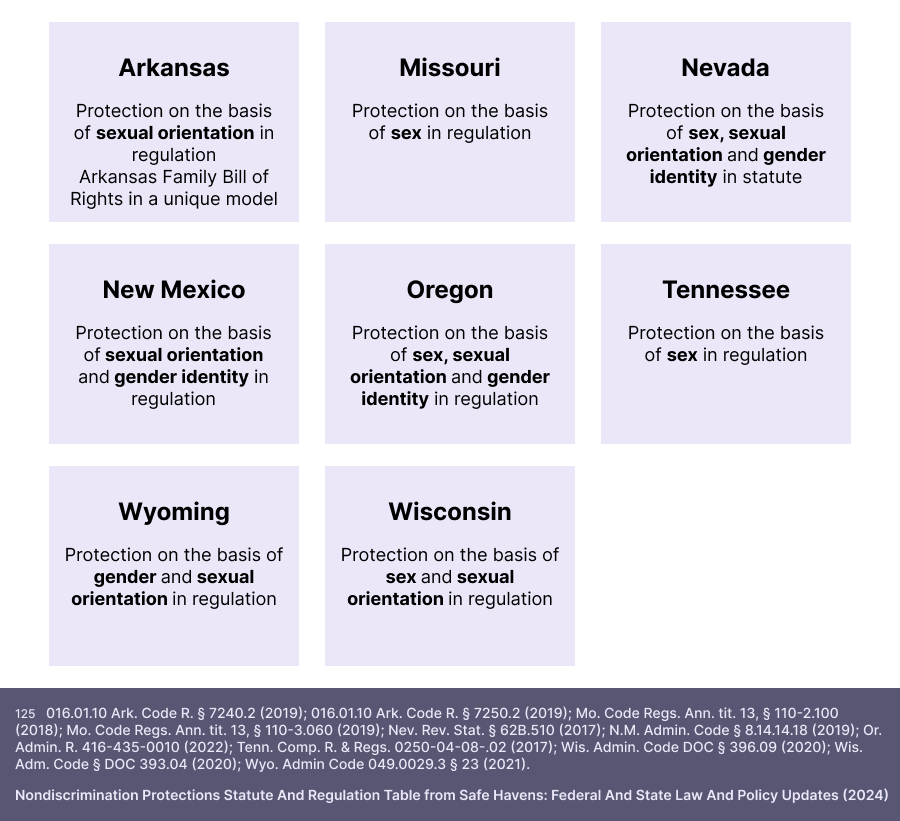

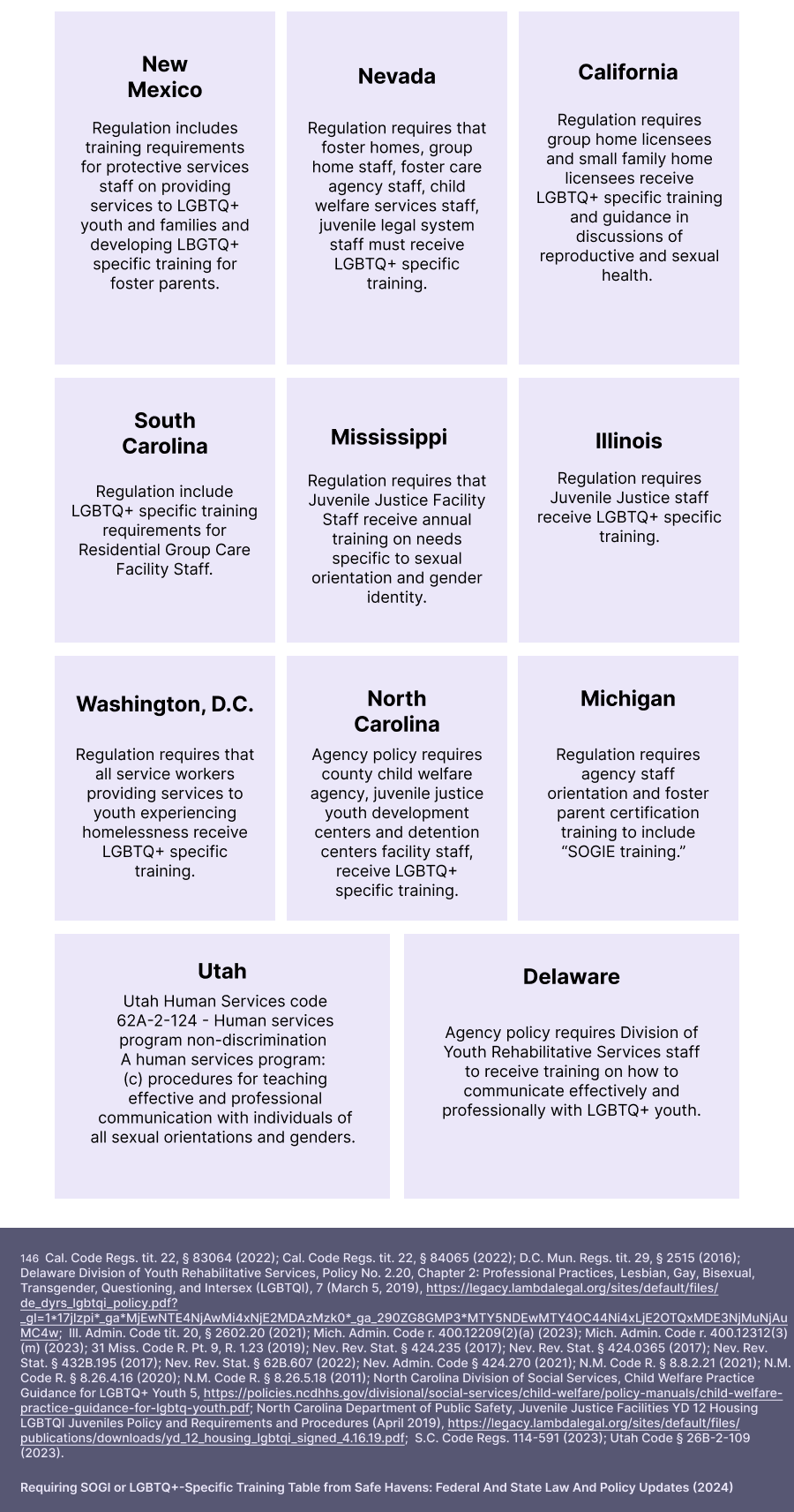

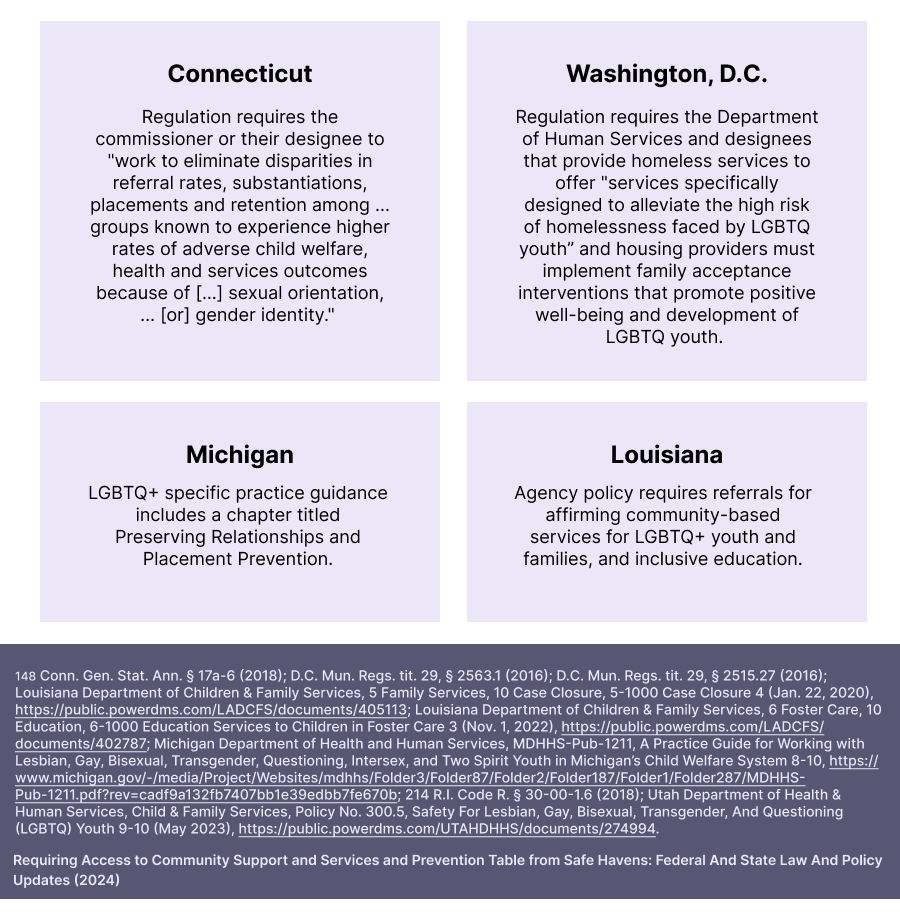

Despite these setbacks, efforts are underway to improve the circumstances for TNGD youth who are involved with child welfare, juvenile legal, and homeless systems. Since the release of Safe Havens I, nondiscrimination protections and affirming agency policy or practice guidance in these systems have increased. For example, 26 additional states have gender identity and sexual orientation nondiscrimination protections in statute, regulation, or agency policy;12 across the child welfare and juvenile legal systems. 44 states now have gender identity nondiscrimination protections in statute, regulation, or agency policy;13 more LGBTQ+ specific practice guidance for agency staff has been developed by child welfare and juvenile legal agencies in collaboration with community stakeholders; more agencies require training for detention staff, probation officers, and child welfare caseworkers; and some states have mandates for prevention efforts and services that promote acceptance of youth by families.

These efforts are a result of strong advocacy and education, and the leadership and increased visibility of, and partnership with, TNGD youth. TNGD youth are engaging in advocacy and systemic improvement efforts, sharing their recommendations and experiences, and asserting their rights in the legislative process, litigation, and agency policymaking. As a result, since 2017:

- Twenty-six states have added gender identity as a protected class in law or policy related to youth in out-of-home systems,14 making the total number of states with nondiscrimination protections for youth on the basis of gender identity 34 in child welfare15 and 37 in the juvenile legal system.16

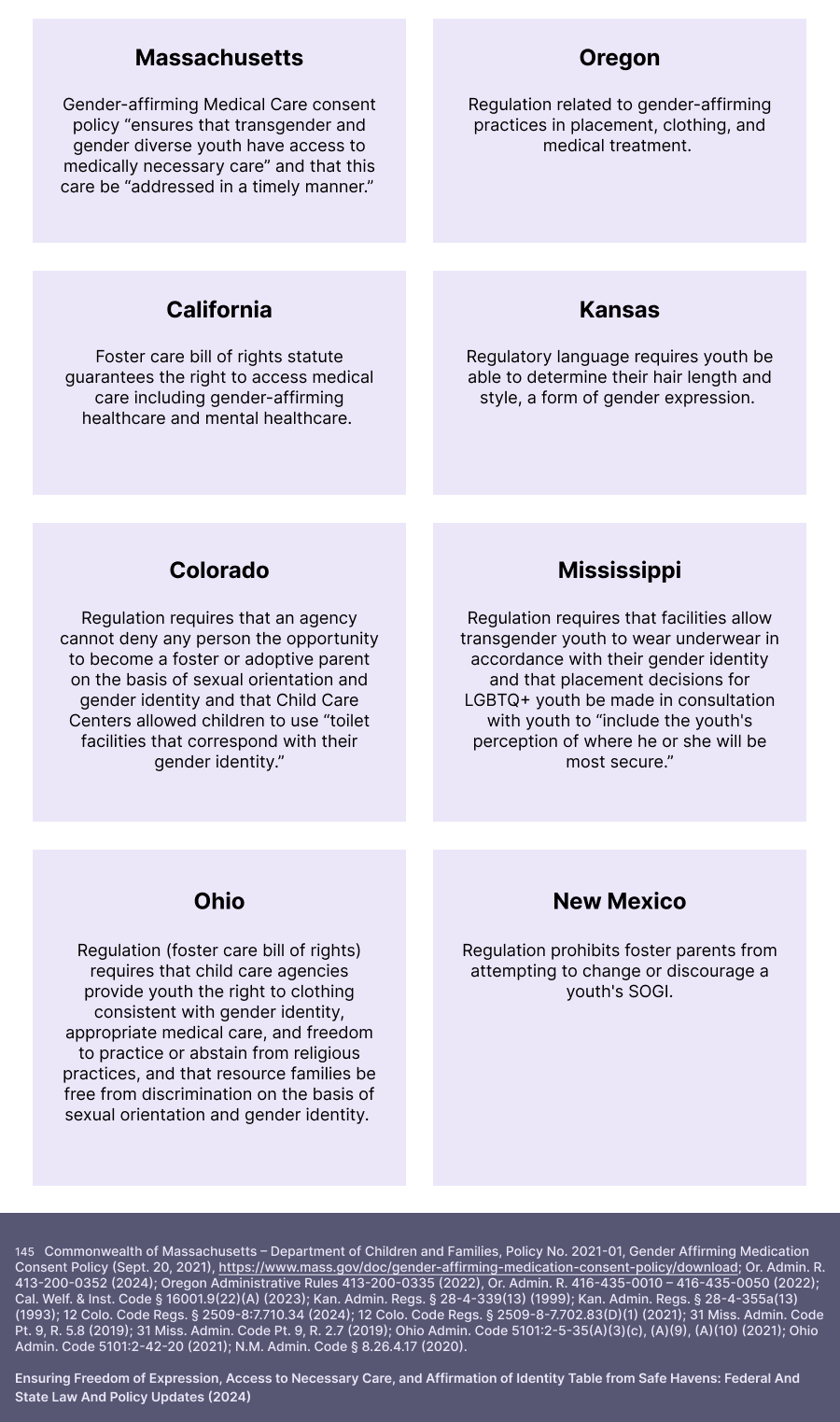

- Sixteen states and Washington, D.C. are providing additional affirmative protection for LGBTQ+ youth in a variety of ways, including protecting the right of transgender and nonbinary youth to access gender-affirming medical care.17

- Twenty states have statewide protections for school-aged TNGD youth.18

- Twenty-three states now allow people to choose an “X” gender marker to reflect nonbinary and/or intersex identities on their identity documents.19

While there has been some progress in law, policy, and practice guidance within child welfare, juvenile legal, and youth homeless systems, there is still more to do:

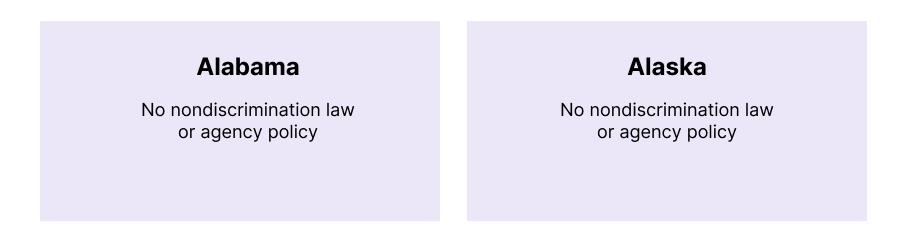

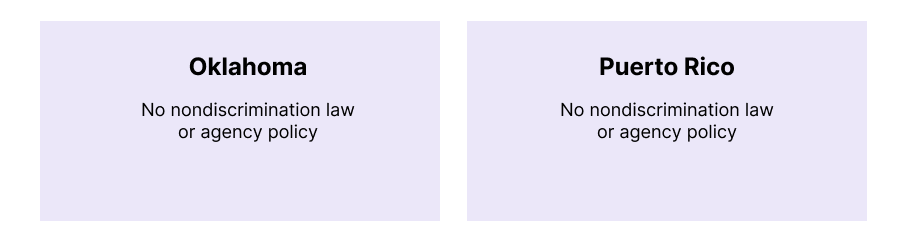

- Child welfare systems in 16 states20 and juvenile legal systems in 13 states21 still do not have explicit protections from discrimination based on gender identity.

- A staggering 46 states have no explicit sexual orientation and gender identity (“SOGI”)-inclusive nondiscrimination law or policy protecting youth experiencing homelessness.22

- Twenty-eight states have laws or policies in place that treat TNGD people differently under the law than their cisgender peers.23

- Nineteen of the 28 states with harmful laws or policies are also states with no explicit protection from gender identity-based discrimination in child welfare or juvenile legal systems.24

- Only four states have any requirement in law and policy to provide services that help prevent system-involvement or to provide services that promote acceptance of TNGD and LGBQ+ youth by their families.25

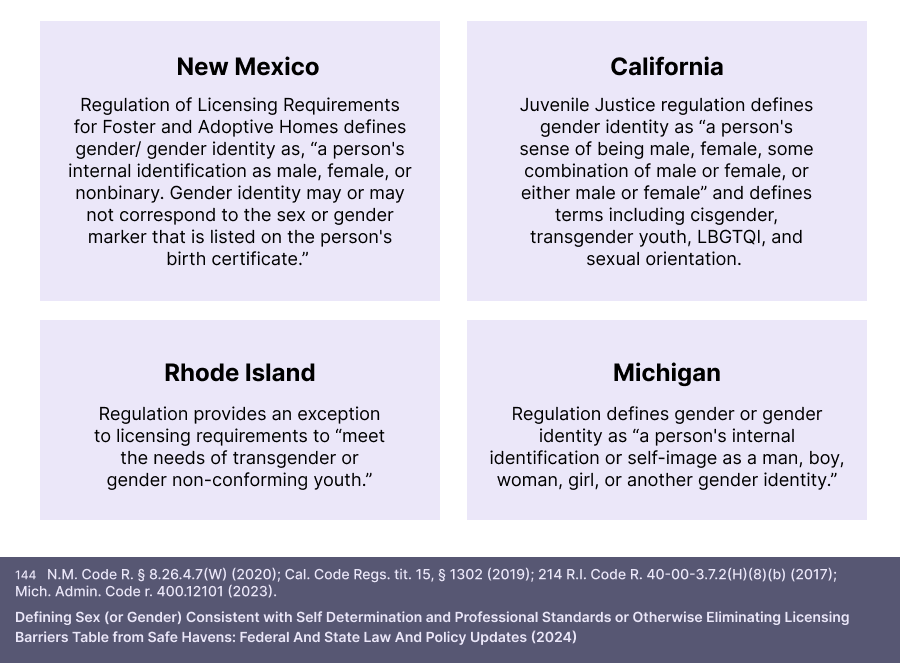

- Only two states acknowledge the existence of nonbinary youth in child welfare or juvenile legal system law, policy, or practice guidance.26

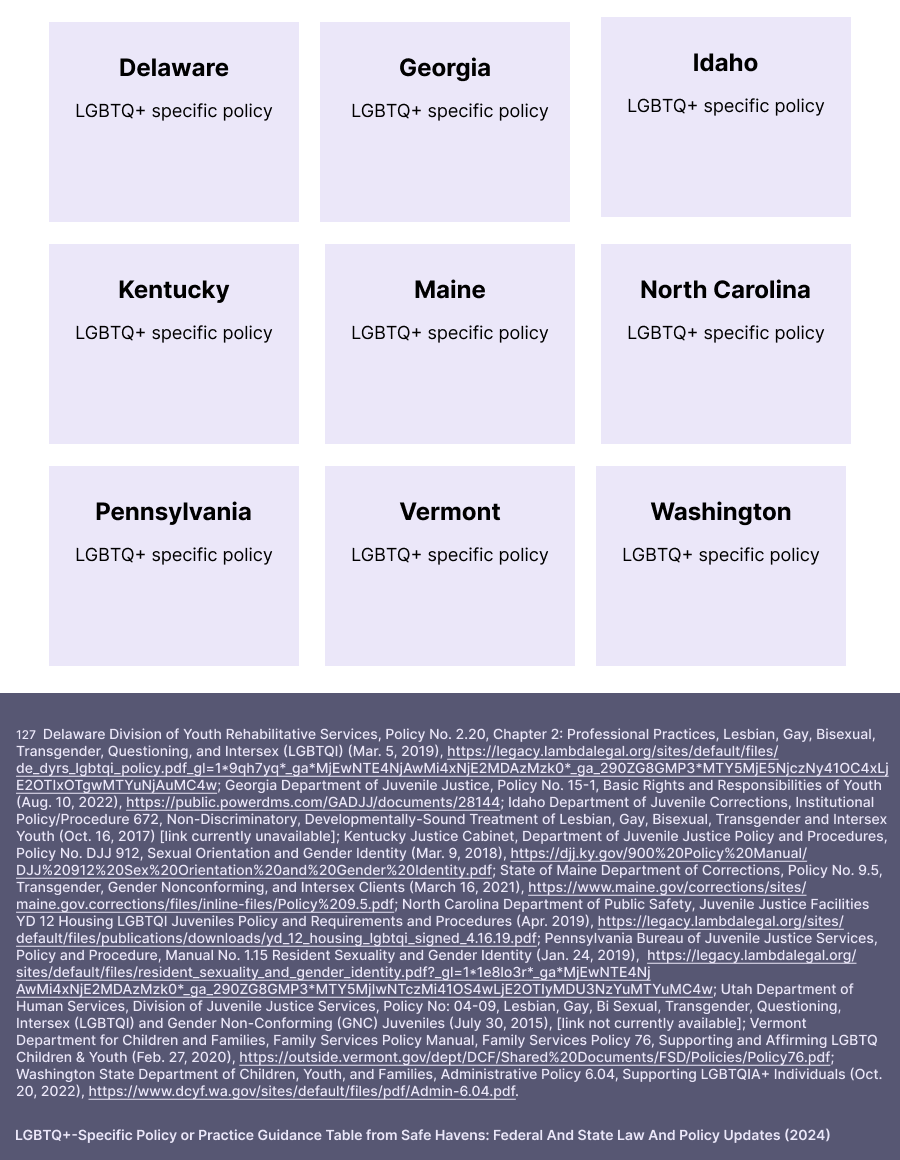

- Only 16 states have LGBTQ+-specific policy or practice guidance for agency and facility staff and contractors in their child welfare systems27 and only 20 states in their juvenile legal systems.28

As Kayden, one of the youth contributors, shared, agencies need clear policies so staff have step-by-step instructions to follow on how to support LGBTQ+ youth. Without explicit protection, clear policies, and a multi-faceted framework of support, TNGD youth remain at risk of serious physical and mental harm, including death – a risk that has grown even greater due to a marked increase in anti-LGBTQ+ laws and policies, which fuel the dehumanization of transgender, nonbinary, and gender diverse people.

Conclusion

Although some progress has been made, it is clear that we have a long way to go. Some states have taken active steps to dehumanize TNGD young people, while other states lack protections that could emphasize universal affirming values such as love, respect, and bodily autonomy. Safe Havens II: We Must Affirm and Protect Trans, Nonbinary, and Gender Diverse Youth in Out-of-Home Systems, includes a call to action from the youth contributors with lived experience; an update of current research about LGBQ+ and TNGD youth; a summary of supportive and harmful federal and state law and policy developments; a description of efforts to prevent system-involvement; and information on the needs of system-involved nonbinary youth. Additionally, we focus on ensuring that accessible, understandable, and safe accountability measures are in place; they are essential for the safety and well-being of TNGD youth.

Endnotes

1. TNGD is used throughout the report, except where cited research uses other terms such as TGNC (transgender, gender nonconforming). Since cultural norms around gender still negatively impact youth who express themselves outside of those norms, the authors emphasize that every individual is unique and there is no one “correct” way to identify or express oneself.

2. LGBTQ+ emphasizes that there are a variety of ways people identify or describe themselves in addition to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning. For example, youth from some indigenous communities may identify as Two Spirit.For more information about the concepts of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (“SOGIE”) or terms youth may use to describe or identify themselves, please see https://cssp.org/resource/key-equity-terms-concepts/. Because people use labels in different ways, or reject labels altogether, the authors recommend that best practice is to honor the language individuals use to describe themselves. Uses of other acronyms in the text are used to reflect research particular to that instance in the text.

3. Brooke Migdon, ACLU says states saw record number of anti-LGBTQ bills in 2023, The Hill (Dec. 2023) https://thehill.com/homenews/lgbtq/4380719-aclu-states-record-anti-lgbtq-bills-2023/; Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures in 2023, ACLU (Dec. 21, 2023), https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights-2023.

4. Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures in 2024, ACLU (Updated June 28, 2024), https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights-2024.

5. Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming; LGBTQ Curricular Laws, Movement Advancement Project, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/curricular_laws; Forced Outing of Transgender Youth in Schools, Movement Advancement Project, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/youth/forced_outing; Bans on Transgender People using Bathrooms and Facilities According to their Gender Identity, Movement Advancement Project, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/youth/school_bathroom_bans; Bans on Transgender Youth Participation in Sports, Movement Advancement Project, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/youth/sports_participation_bans; Bans on Best Practice Medical Care for Transgender Youth, Movement Advancement Project, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/healthcare/youth_medical_care_bans.

6. The authors use “juvenile legal” to refer to the system where youth are charged with delinquencies and may face a range of interventions, requirements, and restrictions on their behavior and liberty including short and long-term incarceration or informal conduct conditions or formal probation requirements. Youth under 18 may be treated within juvenile systems or adult criminal systems depending on the jurisdiction and type and severity of delinquency or crime alleged. The authors do not use “juvenile justice” due to the system being profoundly unjust for youth for a variety or reason, including, the overrepresentation and disparately harmful treatment of youth of color, LGBTQ+ youth, and LGBTQ+ youth of color.

7. Alan J. Dettlaff and Reiko Boyd, Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in the Child Welfare System: Why Do They Exist, and What Can Be Done to Address Them? 692 The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 1, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220980329; Racial and Ethnic Disparity in Juvenile Justice Processing, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, March 2022, https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/racial-and-ethnic-disparity.

8.The Discrimination Administration: Anti-Transgender and Anti-LGBTQ Actions, National Center for Transgender Equality, https://transequality.org/the-discrimination-administration; HRC Staff, The Real List of Trump’s “Unprecedented Steps” for the LGBTQ Community, Human Rights Campaign (June 11, 2020), https://www.hrc.org/news/the-list-of-trumps-unprecedented-steps-for-the-lgbtq-community.

9. See note 3.

10. See note 4.

11. See note 5.

12. CW 15 States: Arizona, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia JL 16 States: Alaska, Arkansas, Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Missouri, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Utah, West Virginia. YH 2 States: Connecticut, Maine.

13. CW 34 States: Arizona, California, Connecticut, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia JL 37 States: Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia.

14. See note 12.

15. Arizona, California, Connecticut, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia.

16. Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia.

17. 17 States with ‘shield’ or ‘refuge’ legislation protecting access to transgender health care”: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington and D.C.”States with ‘shield’ or ‘refuge’ executive order only protecting access to transgender health care”: Arizona, New Jersey; Transgender Healthcare “Shield” Laws, Movement Advancement Project (MAP), http://www.mapresearch.org/equality-maps/healthcare/trans_shield_laws.

18. California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and DC. Safe Schools Law, Movement Advancement Project (MAP), https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/safe_school_laws/discrimination.

19. Driver’s License 22 States: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington Birth Certificate 16 States: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, Washington. Identity Document Laws and Policies, Movement Advancement Project (MAP), https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/identity_documents/.

20. Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming.

21. Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming.

22.Only California, Connecticut, Maine, New York, and the District of Columbia have protections against discrimination on the basis of gender identity for youth served by runaway and homeless youth programs and shelters.

23. See note 5.

24.CW 13 States: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Texas, Utah, Wyoming JL 10 States: Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Wyoming.

25. Connecticut, Michigan, Rhode Island, Utah.

26. “Gender” or “gender identity” means a person’s internal identification or self-image as male or female. Gender identity may or may not correspond to the gender that is listed on the person’s birth certificate. The terms “male,” “female,” or “nonbinary” describe how a person identifies.” Fla. Admin. Code Ann. r. 65C-46.001 (2001); “W. “Gender” or “gender identity” means a person’s internal identification as male, female, or nonbinary. Gender identity may or may not correspond to the sex or gender marker that is listed on the person’s birth certificate.” N.M. Admin. Code 8.26.4.7 (2020).

27.Arizona, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.

28.Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, and Washington.

LATEST RESEARCH

“There was this one staff at the Methodist Home . . . she just made me feel comfortable with being myself. And that was like a turning point. Having an adult who’s letting you be yourself and things like that. It builds up your confidence. So, I feel like she was a very big part of me being comfortable in who I am now.”

— Paris (she/her), Youth Contributor

The youth contributors to this report stressed that although they experienced challenges related to others’ lack of acceptance of their identities, building relationships with adults who affirmed their identities and connecting to peers and mentors in the LGBTQ+ community was absolutely critical for them. Research about transgender, nonbinary, and gender diverse (“TNGD”)1 youth confirms the youth contributors’ experiences that finding acceptance, building relationships with supportive adults, and connecting with LGBTQ+ peers and mentors improves youth’s well-being. In addition to summarizing select research that has been published since 2017 on the prevalence of TNGD and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (“LGBQ+”)2 youth in child welfare, juvenile legal,3 and homeless systems and their experiences and outcomes, the authors provide an in-depth look at available research regarding nonbinary youth. Still, no statewide or nationwide data exist regarding prevalence of LGBTQ+ youth4 in these systems and their outcomes and experiences—systems simply do not collect sexual orientation and gender identity (“SOGI”) data in a way that can be disaggregated and reported for a complete picture nationwide.

TNGD and LGBQ+ Youth are Over-Represented in Systems, are Predominantly Youth of Color, and Have Worse Experiences and Outcomes Than Their Cisgender and Heterosexual Peers.

Child Welfare. Two significant municipal studies confirmed the over-representation of LGBTQ+ youth in child welfare systems compared to the general population:

- New York City’s child welfare agency found 34.1% of youth in its custody identified as LGBTQ+ and 13.2% as transgender.5 A similar study in Cuyahoga County (inclusive of Cleveland), Ohio, found LGBTQ+ youth represent over 32% of youth in its child welfare system; 10.4% of respondents indicated they might have a diverse gender identity; and 67.6% of LGBTQ+ youth reported that they had generally “not been treated very well” by the foster system compared to 44.7% of non-LGBTQ+ youth.6 The New York City study found LGBTQ+ youth in the foster system more likely to be youth of color and to have poorer outcomes than their LGBTQ+ peers, including more frequent placements in congregate placements, more negative encounters with police, and experiencing homelessness.7

- The Trevor Project, which provides support for LGBTQ+ youth contemplating self-harm or suicide, released a 2021 research brief finding that LGBTQ+ youth who had been in the foster system “had three times greater odds of reporting a past-year suicide attempt” compared to LGBTQ+ youth not in the foster system.8 Transgender and nonbinary youth with foster system experience had a 40% chance of being kicked out, being abandoned, or running away due to treatment related to their identity, compared to only 14% of trans and nonbinary youth with no foster system experience.9

Juvenile Legal. A study of first-time offenders in the juvenile legal system showed that nearly one-third self-identified as non-heterosexual.12 Among this group, youth indicated more severe mental health difficulties, more recent post-traumatic symptoms, and higher rates of high-risk sexual behavior and drug and alcohol use compared to their heterosexual peers.13 A study found that for LGBTQ+ youth of color, “marginalization based on SOGIE intersects with racial/ethnic identity-based discrimination to potentiate risk for justice involvement” and that “[t]he overcriminalization of LGBTQ youth—principally LGBTQ youth of color—reflects unaddressed structural racism and chronic, pervasive socially based stigma, discrimination, and victimization based on gender and sexual identity.”14 Promisingly, the authors noted child and adolescent mental health professionals were uniquely positioned and able to change the trajectory of LGBTQ+ youth and reduce system-involvement through “advocacy, education, clinical care, and research” in spite of the “cascade of risk factors for incarceration across [a LGBTQ+ youth’s] life span, including school dropout, homelessness, and high-risk survival behavior.”15

Juvenile Legal. A study of first-time offenders in the juvenile legal system showed that nearly one-third self-identified as non-heterosexual.12 Among this group, youth indicated more severe mental health difficulties, more recent post-traumatic symptoms, and higher rates of high-risk sexual behavior and drug and alcohol use compared to their heterosexual peers.13 A study found that for LGBTQ+ youth of color, “marginalization based on SOGIE intersects with racial/ethnic identity-based discrimination to potentiate risk for justice involvement” and that “[t]he overcriminalization of LGBTQ youth—principally LGBTQ youth of color—reflects unaddressed structural racism and chronic, pervasive socially based stigma, discrimination, and victimization based on gender and sexual identity.”14 Promisingly, the authors noted child and adolescent mental health professionals were uniquely positioned and able to change the trajectory of LGBTQ+ youth and reduce system-involvement through “advocacy, education, clinical care, and research” in spite of the “cascade of risk factors for incarceration across [a LGBTQ+ youth’s] life span, including school dropout, homelessness, and high-risk survival behavior.”15  Youth Homelessness. The risk of homelessness is more than double for LGBTQ+ youth compared to their non-LGBTQ+ peers.19 According to Chapin Hall, youth who identify as “both LGBTQ and Black or multiracial had some of the highest rates of homelessness.”20 LGBTQ+ youth also reported higher rates of exposure to “discrimination or stigma within the family . . . and outside of the family” and were more likely “to report exchanging sex for basic needs . . . and having been forced to have sex.”21 In a 2022 survey, 28% of LGBTQ youth reported experiencing homelessness or housing instability at some point in their lives—and those who did had two to four times the odds of reporting depression, anxiety, or self-harm, considering suicide, and attempting suicide compared to those with stable housing.22 Research continues to demonstrate that TNGD and LGBQ+ youth who are involved with the foster system experience higher rates of homelessness than their heterosexual and cisgender peers.

Youth Homelessness. The risk of homelessness is more than double for LGBTQ+ youth compared to their non-LGBTQ+ peers.19 According to Chapin Hall, youth who identify as “both LGBTQ and Black or multiracial had some of the highest rates of homelessness.”20 LGBTQ+ youth also reported higher rates of exposure to “discrimination or stigma within the family . . . and outside of the family” and were more likely “to report exchanging sex for basic needs . . . and having been forced to have sex.”21 In a 2022 survey, 28% of LGBTQ youth reported experiencing homelessness or housing instability at some point in their lives—and those who did had two to four times the odds of reporting depression, anxiety, or self-harm, considering suicide, and attempting suicide compared to those with stable housing.22 Research continues to demonstrate that TNGD and LGBQ+ youth who are involved with the foster system experience higher rates of homelessness than their heterosexual and cisgender peers.Affirmation, Visibility, and Positive Representation Improve Well-Being Outcomes for All Youth, Especially TNGD and LGBQ+ Youth

Research continues to demonstrate how important identity affirmation is for youth to thrive. For example, use of chosen name and pronouns in four areas of a youth’s life (school, community, family, and among friends) dramatically improves well-being outcomes.23Even if use of chosen name and pronouns occurs in only one of those contexts, youths’ well-being increases.24 Since 2017, TNGD people are more represented in areas of society like politics and entertainment. At least 45 transgender people hold elected office.25 In 2021, Admiral Rachel Levine, Assistant Secretary of Health for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) became the highest ranking openly transgender government agency official.26 In 2022, across broadcast, cable, and streaming television, there are more than 595 LGBTQ+ characters.27 For example, 2018 saw the first openly transgender superhero in a network television series, Supergirl .28 In 2023, Kim Petras became the first openly transgender singer to win a Grammy.29 Seeing LGBTQ+ representation in TV and movies made LGBQ and TNGD youth feel good about being LGBTQ+.30 Further, major social science and medical organizations have reaffirmed their positions that affirmation of identity, access to facilities consistent with identity, and individualized, gender-affirming care when medically indicated after careful evaluation by qualified providers improve the well-being of TNGD youth.31

Negative Depictions in Media and Anti-LGBTQ+ Political Rhetoric is Harmful to Well-Being

A Fenway Institute and Brown University 2020 study found that “frequent exposure to negative depictions of transgender people in the media was significantly associated with clinical symptoms of depression, anxiety, global psychological distress, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in this population.”32 In the 12 months prior to the survey, over 97% of the study participants reported having seen such depictions.33 In The Trevor Project’s 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People, “nearly 1 in 3 LGBTQ young people said their mental health was poor most of the time or always due to anti-LGBTQ policies and legislation” and “nearly 2 in 3 LGBTQ young people said that hearing about potential state or local laws banning people from discussing LGBTQ people at school made their mental health a lot worse.”34 In February 2024, Nex Benedict, a 16-year-old, nonbinary youth with Choctaw heritage, was severely beaten by other students in the school bathroom and died the next day.35 Oklahoma had recently enacted a series of anti-LGBTQ+ laws targeting trans and nonbinary youth and adults.36

Nonbinary Youth Face Unique Challenges

Although in one study, one in four of the LGBTQ+ youth surveyed identified as nonbinary, little research has focused specifically on nonbinary youth in government systems.37 There is, however, increasing recognition of the need to distinguish between binary transgender, nonbinary transgender, and LGBQ+ youth when conducting studies of LGBTQ+ youth.38 The few studies specific to nonbinary youth have focused on their mental and physical health and present mixed findings, but there are indications of unique and worse health outcomes within the nonbinary transgender community when compared to their binary transgender and cisgender peers.39 These disparities reflect minority stress40 generally experienced by marginalized populations, but also speak to the specific challenges nonbinary youth face that cause increased stress, depression, and other negative mental health outcomes. These include the absence of social and family support, a lack of representation, and societal structures that force youth to navigate systems that conform to the gender binary, erasing nonbinary identities entirely. Studies have found that nonbinary youth are more likely to experience negative mental health41 outcomes, including higher levels of anxiety42 and depression,43 lower self-esteem,44 higher instances of self-harm,45 and more frequent suicide attempts46 when compared to binary transgender peers, and higher levels of suicidality,47 a higher risk of cyberbullying, and receiving the least amount of support from family and friends when compared to both cisgender and binary transgender peers.48 While not all nonbinary youth want to pursue a medical transition, those that do are more likely to report facing barriers to accessing hormone therapy49 and receiving less trans-affirming medical care50 than binary transgender youth. Additionally, when compared to binary youth, nonbinary youth reported more truancy and frequency of failing a subject.51 Studies of college students found that, when compared to binary transgender and binary cisgender students, nonbinary youth were more likely to suffer from an eating disorder,52 were more likely to be harassed, sexually abused, and subjected to traumatic events at higher rates,53 and more likely to be misgendered by therapists and health providers than binary transgender students.54 Studies of both nonbinary youth and adults discussed the challenge of navigating their identities within “institutional binaries,” specifically in schools, that cause both hypervisibility and render them invisible: “they are invisible because they are erased by the binary system and its assumptions, while being hypervisible due to [being uncategorizable] within a binary system.”55 While youth are expanding their understanding of gender,56 the widespread lack of knowledge surrounding nonbinary identity and the prevalence of binary gender in society presents numerous challenges for nonbinary youth navigating simple yet critical life steps, such as accessing identity documents that reflect their gender identity, finding safe housing, and showing up as their authentic selves in school and workplace settings. For example, in school settings, “[nonbinary youth] noted that society did not recognize identities outside the gender binary, resulting in a lack of intelligibility and awareness of nonbinary identities in particular, … students were aware they would face an ‘uphill battle’ in terms of gaining recognition and acceptance of their gender[.]”57 Intersecting identities create additional context for youth when navigating acceptance of their identities. In interviews, “Nonbinary Students of Color [are] especially likely to underscore fears of coming out to family.”58

Practices That Support Nonbinary Youth

For nonbinary youth in government systems, having access to affirming placements is not guaranteed, as these systems are often gender segregated and do not provide options for those who do not identify with the gender binary. For system-involved LGBTQ+ youth broadly, “incidents of gender segregation, stigmatization, isolation, and institutionalization in child welfare systems that they linked to their gender expression and sexuality … contribut[ed] to multiple placements and shap[ed] why they experienced homelessness.”59 Studies have recognized that sex-segregated bathroom and placement policies in institutions specifically “render invisible transgender and gender-nonconforming youth.”60 This data reveals a vital need for affirming placement options to ensure better well-being outcomes and interrupt further system involvement for nonbinary youth. While literature on placement in foster and juvenile legal systems for nonbinary youth is limited, research from other settings demonstrates that schools’ efforts to reduce reliance on gender segregated spaces and instead create inclusive, gender-expansive environments can be a model for innovative approaches. Through implementing Gender Support Plans,61 schools and their staff establish affirming practices and collect information to ensure chosen name and pronouns are respected, maintain youth’s confidentiality and safety, and provide access to bathrooms, facilities, and extra-curricular activities that align with their gender identity. Schools have taken steps to reduce the usage of gender-designated bathrooms, whether through building more single stall bathrooms or creating all gender multi-stall bathrooms.62 While there are many struggles facing nonbinary youth, there are also findings that display the resilience of the community and the positive impacts of affirmation on well-being.63 A study that included both binary and nonbinary transgender youth in the Midwest explored strategies of resistance in three contexts: “at an intrapersonal level, strategies included resisting oppressive narratives, affirming one’s own gender, maintaining authenticity, and finding hope[; a]t an interpersonal level, strategies were standing up for self and others, educating others, and avoiding hostility[;] at a community-level, TGD youth were engaging in activism and organizing and enhancing visibility and representation.”64 Social supports for nonbinary youth were found to be very impactful, including providing a safe space for youth to come out to themselves and others, to explore their gender, and to “challeng[e] misgendering or stand[] up to transphobic bullying.”65 This reflects broader studies of protective factors for transgender youth, which have found that even when young transgender people are exposed to high levels of stigma and discrimination, “being strongly connected to their family or their school” lead to “greatly reduced likelihood of negative mental health outcomes.”66

TNGD Youth are Working For Change

As research and data have heightened visibility for TNGD youth, their participation in litigation and systemic improvement efforts has also increased. A transgender girl was a plaintiff in an Oregon lawsuit alleging harm she suffered while in the foster system.67 In a separate lawsuit, J.H., an Alaska Native and Latina transgender girl, submitted a declaration describing her experiences of discrimination in the foster system based on her identity, expression, and culture in support of a motion to stay an attempt by the Trump Administration to gut sexual orientation and gender identity-nondiscrimination protections from federal law.68 J.H.’s declaration was part of a lawsuit filed by Facing Foster Care in Alaska, Alaska’s foster youth and alumni membership organization.69 Many foster youth and alumni groups, such as Facing Foster Care in Alaska, Foster Club, Florida YouthSHINE, and Foster Advocates Arizona, have active LGBTQ+ members or leadership. LGBTQ+ youth have participated in trainings and education for caseworkers, juvenile and family court judges, child advocates, and service providers in record numbers and are sharing their lived experience regarding improving law, policy, and practice guidance with government agencies at the state and federal level.

Endnotes

1. TNGD—transgender (or trans), nonbinary, gender diverse. Used throughout the report, except where cited research uses other terms such as TGNC (transgender, gender nonconforming). Since cultural norms around gender still negatively impact youth who express themselves outside of those norms, the authors emphasize that every individual is unique and there is no one “correct” way to identify or express oneself.

2. We reflect the abbreviation used by a study’s authors. For example, some authors may use LGBTQ without a “+” or only focus on lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and use “LGB.”

3. The authors use “juvenile legal” to refer to the system where youth are charged with delinquencies and may face a range of interventions, requirements, and restrictions on their behavior and liberty including short and long-term incarceration or informal conduct conditions or formal probation requirements. Youth under 18 may be treated within juvenile systems or adult criminal systems depending on the jurisdiction and type and severity of delinquency or crime alleged. The authors do not use “juvenile justice” due to the system being profoundly unjust for youth for a variety of reasons, including the overrepresentation and disparately harmful treatment of youth of color, LGBTQ+ youth, and LGBTQ+ youth of color.

4. LGBTQ+ emphasizes that there are a variety of ways people identify or describe themselves in addition to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning. For example, youth from some indigenous communities may identify as Two Spirit. For more information about the concepts of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (“SOGIE”) or terms youth may use to describe or identify themselves, please see https://cssp.org/resource/key-equity-terms-concepts/. Because people use labels in different ways, or reject labels altogether, the authors recommend that best practice is to honor the language individuals use to describe themselves. Uses of other acronyms in the text are used to reflect research particular to that instance in the text.

5. T.G.M Sandfort, Experiences and Well-Being of Sexual and Gender Diverse Youth in Foster Care in New York City Disproportionality and Disparities, New York City Administration for Children’s Services, 5, 7 (2020), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/acs/pdf/about/2020/WellBeingStudyLGBTQ.pdf.

6.Marlene Matarese et al., The Cuyahoga Youth Count: A Report on LGBTQ+ Youth Experience in Foster Care, The Institute for Innovation & Implementation, University of Maryland School of Social Work, 5-6 (2021), https://theinstitute.umaryland.edu/media/ssw/institute/Cuyahoga-Youth-Count.6.8.1.pdf.

7. Sandfort, Experiences and Well-Being of Sexual and Gender Diverse Youth in Foster Care in New York City Disproportionality and Disparities, 5.

8. The Trevor Project Research Brief: LGBTQ Youth with a History of Foster Care, The Trevor Project, 1 (May 2021), https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/LGBTQ-Youth-with-a-History-of-Foster-Care_-May-2021.pdf.

9. The Trevor Project Research Brief, 2.

10. The National Quality Improvement Center on Tailored Services, Placement Stability, and Permanency for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning, and Two-Spirit Children and Youth in Foster Care (QIC-LGBTQ2S), https://qiclgbtq2s.org/about-the-qic/.

11. National SOGIE Center, https://sogiecenter.org/.